Kaizan Doug Jacobson — Letting Go and Direct Experience

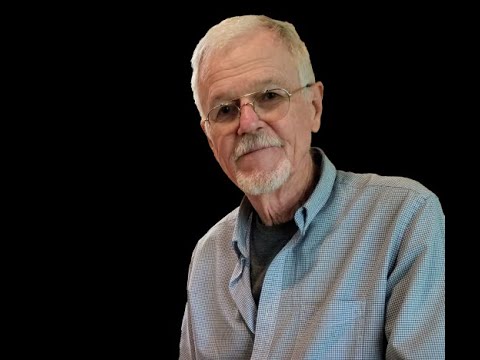

Kaizan Doug Jacobson began practicing Zen in Minneapolis in 1974 with Dainin Katagiri Roshi, and had Jukai in 1977. A householder, father, contractor, and civil engineer, Doug received priest ordination in 2010, and transmission in 2015, from Shoho Michael Newhall at Jikoji Zen Center. He currently serves Jikoji as one of its Guiding Teachers, and also assists prisoners with Buddhist practice. Doug also helps maintain and develop infrastructure at Jikoji, where he enjoys getting his hands dirty as a mode of Zen practice.

Full Transcript

Well, good morning, everyone. Grateful to be here. We're here also in a nature sesshin with Eric. This morning we were up on the ridge to enjoy the sunrise and the fog, the low clouds as they approached us with some rainbow effects. It's one of the inconceivable aspects to me - what makes up a cloud. You know, it's vapor that's condensed and it's not a very big particle. If it is a big particle, gravity affects it and it falls. So these clouds are composed of these infinitely tiny particles that vaporize and condense into these shapes and they reflect light in different ways. And it's always changing. Being in a place where we were close to the dew point, which means it was about 50 degrees up there at this time, it penetrates deeply.

The last part of the beginning gatha was that we are to maintain the Tathagata's teaching. And the Tathagata is each one of us. So the Tathagata's teaching is our full direct experience. I'm talking about my experience on the ridge, but each of you have your full deep experience and that's what is most important. That's what this practice is - our direct experience to work together with others to wipe away many of these notions we have that trap us into our unhappiness or our trouble or our confusion.

The primary action that we learn in this practice of zazen is to let go, let go of our breath that we're in the midst of. At some point you have to take another one, but you have to let go. You can't hold on to one breath. You try to hold on to one breath. It's helpful when you dive into the water and you want to swim underwater for a minute, you hold your breath and maybe let some out, but you have to let it go. And it is as it is with all things. It's essential that we also hold on, grasp again and again to the next breath and experience it fully and to meet this experience wholeheartedly.

Gerow is doing the Han right now. Maybe you get to hear a little bit of it. People are walking to the zendo. Rick's going to share some, a fox tail that they found. Some snakes that he often likes to share. Some direct experience. I don't know how many of you are familiar with or comfortable with snakes, but please come to Jikoji for that direct experience. You will remember it and it opens us to other possibilities.

There is a brief section in William Powell's translation of Tung Shan's teachings. It's number 103 and it goes like this. A monk asked, "What kind of grass is on the other shore?" And he said, "It's a grassy one." And he said, "It's a grassy one. What kind of grass is on the other shore?" And the master Tung Shan answered, "Grass that doesn't sprout." What kind of grass is on the other shore? Grass that doesn't sprout.

When we experience our life fully, we are tossed about and see the grass grow. We see the thoughts show up and they sprout into magnificent forms of fantastic wonderscapes as well as profound hellscapes. And like grass, they go through many changes. In this practice of recognizing first that all things are impermanent and secondly, but interrelatedly is that all things are connected. When we can relax into those two knowledges to our core, we can experience a deep tranquility. It's called nirvana and it's something that is ever present. That tranquility of letting go of all notions and resting in the impermanent and the interconnected as it is. Then we taste the experience of grass that doesn't sprout.

It is really important for us to have thoughts. They come up and they go away. It's important to have them in our Zen practice. Often people think it's important to just shut them down and not have them, that the best way is not to have thoughts. But actually it's the process of letting go of them, to welcome them and let them go. Now some of them, some thoughts that show up, at least for me, this is my experience, is there are some meaningful thoughts that show up that are worth some further investigation because there's insights to squeeze out of them. And then they have to be let go of and even the insight is let go of. I don't know where insights accumulate, but we have them over and over again.

Just as a carpenter who is planing wood takes another stroke and removes a thin layer of wood, the chunk of wood he's working on is slowly wearing away. And even the particles that fall away are disappearing and decomposing and returning to the earth. And he ends up with an object that is of momentary value, a transformed object that has moved from atmospheric particles into that piece of wood to now a transformed piece of utilitarian purpose. And a carpenter cannot hold on to that piece of wood. And that's a good thing to have because his job is to work on the next piece.

So our practice of letting go should be just so appreciated to sit with our thoughts and watch them come and let them go again and again, and then come back to this moment. And through that process, eventually we experience a deep tranquility that brings us to a pool of calm water in our experience that we just can be with. And know that it is part of, it is always here. It is always available. It's just our grasping mind, our averting mind, our mind that brings us trouble.

This ability to welcome what shows up in our life, whether it's in our zazen or in our daily life, and to let it go is the process of birth and death. And when we time after time with just even each breath, watching each breath be born and disappear, we can, in this repeated experience of birthing and deathing of what we're doing, it brings about a fearlessness in us of meeting what shows up. We know we can do it. We can know we can show up for all of it. And when we do meet our death, we can meet it as it is, that whole process of our existence, transforming into what happens. But it takes practice. It takes repeated use of this body, repeated experiences of it. And through that, we become unafraid of what shows up next, in the next moment.

In "Opening the Hand of Thought," Uchiyama Roshi says that this Buddhist practice has deep foundations that refer to the reality of life prior to all definitions. The life prior to all definitions is our direct experience without labeling, without discriminating, without selecting. This experience of zazen helps us to develop the power that is beyond words and ideas. Definitions do not apply. It is just our direct experience again and again.

When I was in my early 20s, it's so fun to be young and vital and on the path to seek and find again and again. And I was fortunate enough to run into a Zen Master who, his wholehearted practice was visible. And when he would say, "just this it is," there was something transmitted in that, that a truth, an ungraspable truth, an inconceivable truth was being expressed. And I knew that there was something important going on here and I better pay attention.

I don't know if anybody else has had this experience, but once you closely pay attention to what's going on in zazen, and realize how important it is and how important it is to persist and attend zazen and do it over and over and over again, I don't know, to me it felt like the biggest mistake I had made. Because, you know, when you finally find out what you have to do, then you can't be a kid anymore. You gotta pay attention. You gotta do it. But I still feel like a kid, so maybe that notion of being a big mistake isn't so... Well, there is something to that.

Because part of each of us, our existence is made up of, even our being born is an accident. There is, their parents might plan to have a kid, but they have no idea what kind of kid is going to show up. And so just in that, there is an accidental happening that arises. And we can look at just about everything that we engage in is not generated by our doing. It is just showing up in our life. Even where we put our attention a lot of times is accidental. And some people can remain very focused and put their attention directly on what they want. And some of us, like me, have an easily distractible mind, which in an evolutionary sense is useful in community. There are people that need distractible minds in order to help do certain parts of what community arises in community.

So please enjoy the accidents of your life and relax in them and bring a fearless quality to it. A fearless quality that is based on a deep trust in yourself, in the process of self-selfing that we do. We talk about no self, no fixed self. We are each a flowing, in motion, processing being that all we can do is pay attention to this life and take best care of it.

So I'm going to stop there and would like to hear what you are thinking, what's coming up for you, what's meaningful for you in this time, this day.