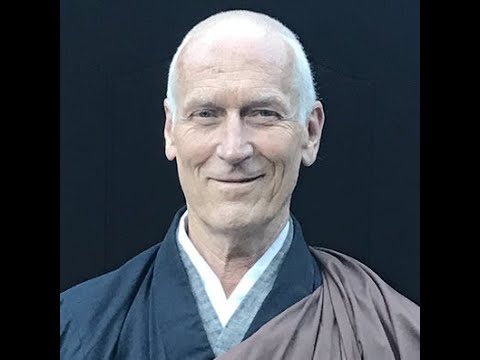

Ben Connelly — Mindfulness and Intimacy: Balancing Boundaries and Boundlessness

Mindfulness is an ancient and powerful practice of awareness and non-judgmental discernment that can help us ground ourselves in the present moment, with the world and our lives just as they are. But there’s a risk: by focusing our attention on something (or someone), we might always see it as something other, as separate from ourselves. To close this distance, mindfulness has traditionally been paired with a focus on intimacy, community, and interdependence. In this talk, Ben Connelly shows how to bring these two practices together – bringing warm hearts to our clear seeing.

Ben Connelly is based at Minnesota Zen Meditation Center in Minneapolis. He travels to teach across the United States.

Full Transcript

Greetings. More bows. Why not? More embodiments of gratitude, love, appreciation, and respect. That's not going to bring you down. It's really nice to see you. I have a lot of friends in this group. To all of you that I've known for some time, I'm happy to see you. And there are folks I may or may not have met. I'm happy to see all of us here today. Thanks for bringing me into the fold. I feel like I get to be, through the power of Zoom, like a sort of honorary member of this community.

You're really missing out because, I know in Zen you can't miss out. You're already intimate with everything. But you're missing out because, overnight here it was in the teens and foggy. So we have what's called a Rime Frost. All the trees are glittering in the sun. I thought I'd try and show it with my laptop, but there's no way you can see it. You look out the window, it's just this blur of white. So I'll just have to use my literary capacity to convey to you how beautiful it is here. And I've been where you are. And I know that you live in a very beautiful place. So it's good to notice because you may have also been noticing things that are making you uptight, freaked out. This year has been a year like no other. And this week has been one that for many people has been really stressful.

So however you are, I'm glad you're here. I'm glad you're here. And we can be pretty sure it's going to change. I just watched a little video of Norman Fisher last night, one of my favorite Zen teachers. He said, you know, you're alive. It's really amazing that you have problems. And the only reason you can be alive is you have problems. And the only way you can have problems is because you're alive. So you might as well appreciate what's here, even if it's hard.

So I'm supposed to talk about mindfulness and intimacy. And this pertains to appreciating life and appreciating problems. Being able to meet reality with some joy and some lightness. And it's bringing to mind a line of James Baldwin who wrote, we are capable of bearing a great burden once we realize the burden is reality and come to where reality is. Sounds pretty Zen. Of course he wasn't into Zen, but he was insightful.

So mindfulness and intimacy. I gave a talk called mindfulness and intimacy at Santa Barbara Zen Center last year. So I'm just going to play the recording of that and I'll see you later. Not so. I am not going to use any of the same notes or really cover the same particular material. I'll be dealing with the same thematic material. If you want to, if you weren't there, you want to see kind of like how I usually approach really framing the subject as it's expressed in the book that was published last year or two years ago or something. There are many versions of that talk online. They're not hard to find because I gave it at like 50 places. So today it'll be a little different.

Mindfulness is being aware of things in a way that's beneficial. Mindfulness has a kind of an older definition, which is just like what you're aware of or focused on. So, you know, a hundred years ago, you're like, you should be mindful of closing the door quietly, a conventional meaning. But now we've got so much Buddhism in Western culture that we have a pretty shared definition. So yeah, being aware in a way that's beneficial, being aware of things in a way that's beneficial.

Intimacy, I'll be using here in some conventional ways and some unconventional ways. Intimacy, you know, common synonyms would be closeness, familiarity, inseparability, belonging. So those ring true. That's what I'm talking about. Belonging, inseparability, closeness, familiarity. Many times in the ancient literature of Zen, they say Zen is a family style. Family style. It's about intimacy. But I will be using intimacy also in sort of an unconventional way. And I would say deeply related to, if you're into Buddhism, some of these things may sound familiar, like sangha, non-duality, emptiness, interdependence, things like that. All are deeply related to the way that I'll be talking about intimacy.

This framing is not an innovation. I sort of try and not be too innovative when I'm teaching Buddhism. It's a pretty long-standing tradition. And I feel like my position in speaking, when I'm speaking to a Buddhist community, is as a Buddhist teacher. And so it's important to me to be balancing an authentic and immediate expression of what's beneficial, given who we are together in this moment as a group, with honoring and respecting the way through which I am empowered and the people, the human beings, most of whom have lived in Asia over the last couple thousand years, who have created a tradition through which I can be empowered.

Mindfulness and intimacy are another way of thinking of it. They're a fresh way for me to talk about the basic Yogacara modes of practice, which are Vipassana and Samatha. Vipassana being a discerning way of viewing the world, where you're looking at the world insightfully. Vipassana sometimes translated as insight, understanding how to engage with it in a way that's most beneficial. And then the other side is Samatha, which is basically non-duality. It's abiding in something that is beyond any of your ideas about it, but doesn't exclude your ideas about it, and doesn't exclude anyone or anything. This material takes a little while to sink in.

So anyway, that's what's kind of a basic frame. And so I'm going to kind of move and talk about mindfulness for a minute, and I'm going to talk about emptiness for a few minutes. I'll see what happens.

Mindfulness, you may have heard of, you know, it's one of the root practices of early Buddhism. It's now like a trend, and all kinds of versions of it are emerging. That's pretty amazing. I was giving a talk to a big group of recovering people, recovering addicts and alcoholics a while ago, and during the Q&A, someone said, oh, I really appreciate you talking about this in some detail, because I'm a therapist, and I teach mindfulness to all my clients, but I've never practiced or had any training. Wow! USA, USA! This is how we do it. It's like, you're an expert immediately. No problem.

So anyway, this is happening. I bring it up, so we just know that it's real. But I do think mindfulness is very simple in some regards, but it's also a very deep and complex tradition. The basic root texts on mindfulness are the Pali Canon, Four Foundation of Mindfulness texts, and the Mindfulness of Breathing Sutra. And these sutras are about bringing very particular aspects of your experience into awareness, and being aware of them, and developing ongoing awareness of them.

Everybody's aware of certain things all the time. Most people who start meditating find out they're mostly aware of the... You're not aware that you're having a stream of thinking. You're just absorbed in a stream of thinking. So there's no meta-awareness. It's just like you walk down the street, you don't know you're walking down the street, you don't know there's rime frost, you don't know anything else. You just know, oh my God, the United States is in a cataclysm, and I give up, or those people are terrible, or whatever it is, whatever your mind is doing.

But mindfulness is about developing awareness of specific things which are conducive to liberation from suffering. Now, these things are mindfulness of body, mindfulness of feeling, mindfulness of mind, and mindfulness of phenomena. So it's just stuff that's already happening. It's not like you're attaining some magical state outside of your own experience. It's just really noticing particular things that will actually work for you. Because generally speaking, the human mind is not doing things that really help us that much. And if that seems surprising to you, well, you can turn on the news and tell me if what everyone is doing is really working out for everyone. There's a lot of suffering.

Sometimes I'll talk a little bit flippantly, but it's true. There's a lot of suffering in the world, and we carry it with us. And Buddhism argues that the most important thing to focus on is our position within it, to remind us that we can always do something beneficial. And then once we have that idea, then it's like, well, let's turn the lamp within and see what's going on here.

So we have this mindfulness sutra. The basic quality of mindfulness I would call cooling. It's a very cool, detached, dispassionate thing where we sort of notice as an observer, oh, this is happening. So there's a boundary. It's a very bounded activity. And I'm just going to read you a couple of little parts, the four foundations of mindfulness sutra, and give you some flavor of this.

So after we have developed mindfulness of body at some length, which I cannot possibly recommend enough, I would encourage you to develop mindfulness of body in meditation when you're sitting zazen, and when you're walking, and when you're doing dishes, and when you're dancing, and if you don't dance, you should try it.

Anyway, so having established mindfulness of body, second foundation of mindfulness, feelings, here we're in mindfulness of mind from the Satipatthana. And how, monks, does a monk dwell contemplating mind? Here, a monk understands a mind with desire as a mind with desire, and a mind without desire as a mind without desire. He understands a mind with aversion as a mind with aversion, and a mind without aversion as a mind without aversion. He understands a mind with delusion as a mind with delusion, and a mind without delusion as a mind without delusion. He understands a contracted mind as a contracted and a distracted mind as distracted.

And then I'm just going to shift ahead to, in the fourth foundation of mindfulness, mindfulness of phenomena, a very similar language. A monk contemplates phenomena in terms of the five hindrances. When there is sensual desire in him, a monk understands there is sensual desire in. When there is no sensual desire, he understands there is no sensual desire in. When there is ill-will in him, he understands there is ill-will in me, and when there is no ill-will in him, he understands there is no ill-will in me, and so forth. There's various other categories.

Just trying to give you the flavor. So this is not super exciting. It's almost clinical. Just like, I'm just seeing this. Now, normally, I don't know, when I came to Buddhist practice, I was like, there's ill-will in me. Then I was immediately, proof that I'm a terrible person. Or I wouldn't even get there because I was just like, that person is horrible and they're a moron and they need to shut up. So I wouldn't notice there's ill will in me. I just knew that the person was a moron and was terrible and should shut up.

This is really about being aware of specific emotional aspects of experience with a dispassionate mind. Being able to just be like, all right, this is here. My space is big. Now, some people think this is a little too cool. That's why I'm talking about mindfulness and intimacy. But it's actually very helpful to bring this flavor into your practice, because it is very cooling.

So in the Mahayana, of which Zen is an outgrowth in Buddhist terms, we don't talk about dispassion as much. The literature doesn't. It talks about compassion more. But dispassion is valuable. It's valuable to have that ability to just be like, all right, things are getting a little too hot. I'm just going to make a lot of space and notice that this is here. So the space in which our emotions exist gets bigger because we're not identified with them, we can just see them. This is a way of caring. It's a way of caring.

So being cool can help. You know, when your friend is totally freaking out, it doesn't always help them to just be like, I'll just freak out with you just as much. You know, sometimes it's good to just be like, oh, I'm really hearing you, but I'm not adding anything to this fire. Right. I don't know about you. I'm a recovering drunk, so I spend a lot of time in bars. You know what I've noticed? People who go into breakup fights end up punching people a lot. It's like you see two people have a conflict and then it seems to be dudes a lot of the time. And more and more men are sort of gravitating to the locus of this conflict. And somehow it's not always the case. It's possible to really be disarming, but it's very frequent as we move into that to be adding.

So mindfulness has this flavor of really being present to suffering without adding anything, just seeing. And this can be really, really healing. It can be it with all these foundations of mindfulness, everything is done internally, then externally. That is to say, I learned to notice others ill will here. And then as I get that ability to just be like, oh, this is what ill will is like. And I really know how I feel instead of just being up in my head. Then when I meet someone else, I have that capacity to be like, oh, yeah, you are experiencing ill will. I can be here with you. Because without that capacity, we tend to either leap into their story and add to it or maybe be very averse. I'm not even going to talk to you. You seem sad. That's unpleasant for me. Oh, thank you. Whatever. We can build this ability to just be with reality, when reality is emotional, without adding anything.

So cooling, cooling. And this, you know, this to me, this just ties deeply to a boundary, boundary way of being. So boundaries are really important. You know, when I'm in my family and something's going on that's really weird, I can be like, oh, I'll get on the phone and call my brother and try to get my mom to do something. That's not great. It's way better to be able like I'm talking to my brother. I know what is arising in me. I'm trying to be present to what's arising in him. With some space, some of this cool, boundary compassionate action, because it is compassionate, because it's effective at alleviating suffering.

OK, so you may need to affect some I don't know how you're doing there, but a lot of people I know is like it's like all they're all they've done for the last 72 hours is click on links. But terrible things that are happening and really harmful and frightening and dangerous things. And, you know, it's good to be informed. It's good to be mindful of the social context in which we live. But it's good to be boundaried and be like, oh, well, you know, I'm just like compulsively doing this thing, I don't even know why. I can just stop learning about the news and use mindfulness to learn about the reality of your experience right now. Really important. Really important. Because otherwise, we're just the same. Dudes at the bar running in to stop the fight. I'm not saying you shouldn't intervene to stop fights. I'm just saying be careful. Are you adding?

I'm going to talk a little bit about the intimacy side here. So mindfulness is this could you read the early Pali Canon Sutras and these monks and these nuns and these laypeople are just like, They're just so peaceful, never getting activated. They're just there with people. It's really beautiful. It is really beautiful. And you can feel the flavor of the stillness and the quiet and the presence of the people in the stories. So it's great. And there's a lot of intimacy in these stories. These are people who are relating closely to each other.

So intimacy is fun when I'm talking about it now, because it will be non-dual. So I'm going to set it up in opposition to mindfulness, but it completely includes mindfulness. And I'm going to set intimacy up as like kind of the wondrous non-dual engagement with the universe, which is completely free of suffering. But it's also really messy. Intimacy is very messy. Have you noticed what happens when you actually are willing to love people? Ah, jeez. Oh, my goodness. You know, I tried to stay away from people and it didn't it didn't I couldn't. And it didn't make me happy to try and always hold people at arm's length, not because I was mindful and I had good boundaries, but because I was scared of them and I didn't want to deal with the pain of the messiness of real human relationships. And so intimacy is about saying, you know what, I'm going to go, I'm going to like do this.

I'm going to acknowledge and fully move into my being a part of this relationship. And the great thing about Mahayana Buddhism is it says you're always only relationship with everything. So there's like infinite room to expand your ability to dive into the messiness of the universe.

Another way to think about this is boundarylessness. Boundarylessness is a popular theme in Mahayana Buddhism. It's like just dissolve the distance between you and everything else. It really can be very moving. But I got to say, the reason I talk about mindfulness and intimacy is we also need good boundaries. So a lot of people will kind of try and leap into boundarylessness and they won't have the capacity to do that in a healthy way. And again, they're there in that bar throwing one person down in order to stop them from hurting somebody. This may be an overextended metaphor, but hopefully you get what I'm pointing towards here.

So I'm going to read you a little poem. This is from one of my favorite Donald books, Daughters of Emptiness. And this poem actually kind of is like between mindfulness and intimacy. It's got it all. Suddenly, as this is a poem by a woman named Miao Zhang, the 11th century Chinese Zen nun.

Suddenly, I have made contact with the tip of the nose.

And my cleverness melts like ice and shatters like tiles.

What's the need for Bodhidharma to have come from the West?

What a waste for the second patriarch to have paid his respects.

To ask any further about what this is and what that is

would signal defeat by a regiment of straw bandits.

I'm aware this might seem a little esoteric. I made contact with the tip of the nose. This is basic, many different meditation methodologies. The location of the breath is in the nose we notice in the nostrils. Generally speaking, I recommend the belly, the lower abdomen, which is more common in Chinese meditation systems and Japanese and Zen. But the nose, to know the nose. Because you're sitting here in sesshin, you can really know right in front of my face. It can't be any farther away.

A monk asked Xuanzha, why is it? What is it? Monk asked Xuanzha, what is it? And why is it so hard to realize? And Xuanzha said, it's too close. So this nun has this great realization by making contact, which the thing which is the most close thing there could possibly be. It's her own body and it's in her field of vision. Wow. Total intimacy is already here, but we can actively make contact with it. That's what practice is about. To actively make contact with the non-duality, the total connection, the interdependence, the inescapable togetherness that's already here.

So she does this and she talks about some kind of weird stuff in here I don't want to get into, but I do like my cleverness melts like ice and shatters like tiles. Yeah, messy, messy. But at the end, she says, you know, to ask any further about why this is and what that is would signal defeat by a bunch of straw bandits. Basically, how can I sum this up? What she's talking about is when we're making discernment, when we're saying, oh, I'm noticing this and not that, I'm picking and choosing out a reality, what I'm going to focus on, I'm going to have a boundary position and I'm going to stay here on my side and in my lane and I know what things are. We have to make all those distinct things in order for them to exist. They only exist because of our own discerning mental activity. They're straw bandits. None of them can hurt you. It's all the activity of mind. And she's just like, I'm putting all that down and realizing something incomprehensible, which is that you're alive right now. What a trip. Don't forget that it's. Look around. Just in your field of vision, thousands, millions of things every instant. You don't have to figure any of them out. Just be boggled. And then she's like, oh, I'm not being defeated by reality. It's not a bunch of stuff that comes at me and I have to figure out and control and manipulate. I'm just here in contact with what is directly in front of me. Is both in front of me and is me. The tip of the nose. Is it you or is it something that you see? Is your body yours or is it you? Is your mind yours or is it you? Nonduality. It's just ideas.

You know, we sometimes the thing is like this idea of intimacy, and I'm talking about in like some kind of crazy Zen ways here, but you know, one way to notice if you're realizing, I would say a great my favorite scale for like how much am I realizing intimacy is. Is the degree to which you're trying to control an external circumstance. Direct proportional thing. The more I'm trying to control an apparent external circumstance, the less I'm recognizing intimacy and the less I am, the more I'm recognizing intimacy. Now, this doesn't mean you're not being like active, but like say back to the family, you got a family conflict or something difficult. You know, can I tell someone in my family, this is really difficult for me and I feel angry that you've done this, whatever it is, without expecting them to do anything or to try to control them. But just to realize the connection that we already have.

So this way of intimacy does not preclude doing difficult and messy things and showing up in contexts where things are fraught. It's not denying them or getting rid of them, because that wouldn't be non-dual. It wouldn't really be intimate. It would just be like imposing your thing on them. Intimacy is non-violent. It's non-domination. And I am really into inviting people into realizing their intimacy with themselves and using mindfulness to be able to do that in a way that they can tolerate. So if you're doing pretty well, it's pretty easy. But sometimes things are really fraught and we need to use those tools that give us some space. And then we can find intimacy with other people, with teachers, with friends, with family, with birds, dogs, flowers, door handles, beaches, rime, frost. It's all an opportunity. And we can also find intimacy with this very fraught social environment we live in where people are suffering for so many reasons and people are causing harm. And we can enter into that without denying it or pretending we're separate from any part of it and just find a way to do something beneficial. You can do that. You can do that. And then when you get exhausted and you're like, this is too frustrating or I'm too angry, then you can pause and you can come back into mindfulness and do something that will give you a boundary space for healing and for caring for what's arising.

So I'm just going to read you maybe one or two more things. We'll see. So here's a poem from Daughters of Emptiness by a poet who is a nun whose name is Xian. We don't have dates for Xian, but I think it's like a middle of the last millennium. Oh, as I read this, the last line will talk about straightening o cases. So a case says the full body robe that priests wear in China and Japan. They call it something different in China. And robes, like in the Zen tradition, are very finicky. And so you see priests are always kind of, you know, cloth management. I think Wendy Nagao at ZCLA used to call it cloth management training. So they actually give you something which is kind of a little bit frustrating and weird and annoying that you live with and wear on your body because intimacy is messy and you practice and then you learn to love just taking care of simple things beautifully. So anyway, on a spring night the moon with master of Lanying.

The luminous moon drifts by so lightly.

The sutra hall lies silent without a sound.

Bits of moonlight pierce the cracks between the bamboo.

Its round refulgence perches in the intersecting pine branches.

The dew dampens the nests filled with noisy swallows.

The wind combs the grasses filled with croaking frogs.

I sit with the master after the ceremony is over.

As face to face we straighten our o cases.

We slow down. Slow down and you may realize this intimacy. And when you take the time to slow down and realize this intimacy, you create the context for intimacy to be realized for everyone. And then wherever you go, you have this connection. And then we forget. And then we can say, oh, I want to remember. Mindfulness means remembering. And then we try and be in relationship and we get really upset. And then we can use mindfulness to care for our emotions. And then when we're a little more settled, we can come back. But we never left. Because intimacy is all that there is. Thank you for your kind attention.