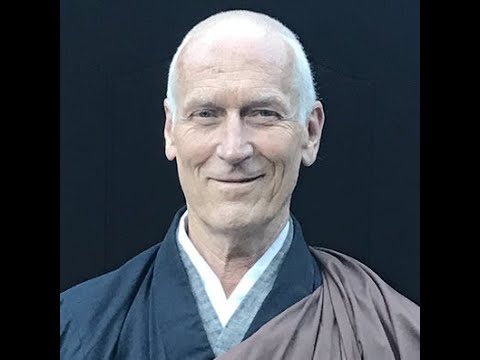

Joel Kyoshin Jokyo Feigin — Essence of Purity: Remembering Sojun Roshi

Joel Kyoshin Jokyo Feigin is a long-time Zen practitioner: in 2017 he was ordained a Zen priest by Sojun Mel Weitsman Roshi at Berkeley Zen Center and given the dharma name Kyoshin Jokyo. Joel began Zen practice with John Daido Loori Roshi in 1987 and has also studied with Maezumi Roshi at ZCLA and Josho Pat Phelan Roshi at the Chapel Hill Zen Center; his studies with Sojun Roshi began in the mid-1990’s. Joel has been practicing at Berkeley Zen Center since the 1992. He is also an emeritus professor recently retired from UCSB, where he taught composition in the Music Department.

Full Transcript

Mel was called ordinary. And that's true, we all call him ordinary with a big smile. Ed Brown began his statement there, "Mel seems so ordinary," and brilliance flooded me. So Mel was just Mel and that was his teaching.

Mel was born in 1929 in LA and grew up during the Great Depression. His parents were shopkeepers and there was very little money to go around. I don't think Mel ever went to college, but he went to the Art Institute of San Francisco and studied painting with Clifford Still, who was one of the great abstract expressionists. I've only seen one painting of Mel's and it's in the community room at Berkeley's Zen Center. Very beautiful, it reminds me of Rothko.

Mel was in the Bay Area in the 50s and got big time into the beat scene. He knew poets and musicians, classical and jazz musicians, and he smoked a lot of grass and was just totally on that scene. To support his painting, he painted houses and boats and drove a cab. As a cabbie, he would talk to the people he was driving for and sometimes they'd pull over because they were into the conversation. The people Mel picked up found talking to him very helpful and very comforting, and Mel enjoyed it.

But Mel was searching. He loved painting, but he hated the business of art. He read Martin Buber and loved it. He really loved Buber's sense of the spiritual life, spiritual community. So he looked for a rabbi and he found Suzuki Roshi.

The story goes that one night Mel and a friend were smoking grass. Around four in the morning, one of them said, "Hey, there's this Japanese Zen teacher around and you just show up at five or something and you can do zazen, isn't that awesome?" They probably didn't say awesome then. I don't know what they said in the 50s or early 60s. So they said, "Hey, we have just enough time to go and do this."

They went and Suzuki Roshi greeted them, taught them how to sit and they sat zazen maybe half an hour, I don't know. Then they chanted the Heart Sutra three times in Japanese and they probably bowed, a regular service. As they left, Suzuki Roshi bowed to his students. Suzuki Roshi bowed to Mel's friend and Suzuki Roshi bowed to Mel and their eyes met. Suzuki Roshi was there and Mel was there and Mel was at home.

At that point, his life was zazen working with Suzuki Roshi. He would do morning and evening zazen with Suzuki Roshi. He would go to talks, he would do dokusan and he also got to know Katagiri Roshi and Kobun Chino Roshi very well.

When Suzuki Roshi opened Tassajara, when they started the monastery, they did sesshins. Mel was up there for all the sesshins, of course. There was one sesshin where it was very, very hot and hot Tassajara in the summer is very hot. Everyone was sweating and the robes got drenched and it was real hard not to squirm. I think pretty much everyone at the sesshin felt they hadn't done very well, whatever that means.

After the sesshin was over, Suzuki Roshi called Mel over to speak to him. Suzuki Roshi said, "I want you to join our order. I want to ordain you as a monk, as a priest." And Mel said, "Okay." Mel said okay to everything. It was very Mel. And then Mel said, "Well, when is this gonna happen?" And Suzuki Roshi says, "Well, when I'm ready, when you're ready." And so that was that.

Around the same time, Suzuki Roshi asked Mel to found a Zen center in Berkeley where Mel was living. So Mel did. He converted his attic into a zendo and people came and sat. Mike Blanche Hartman came, Norman Fisher came. I mean, all sorts of people came. Of course, at that time, they were just regular folks as they still are.

In that attic zendo in 1968, Suzuki Roshi ordained Mel. He cut off Mel's hair. He gave him the Dharma name Sojun, essence of purity. And he gave him an okesa. So Mel was now a priest.

Mel went off to Suzuki Roshi after the ceremony and said, "Well, now that I'm a priest, what happens? What do I do?" And Suzuki Roshi said, "I don't know. Just ask Katagiri over there." So Mel went and asked Katagiri. And Katagiri said the same thing. "I don't know." And he said, "Why don't you ask Kobun Chino?" So Mel went and asked Kobun Chino. And Kobun Chino says, "I don't know." And so Mel didn't know, which is a beautiful way to start pretty much anything.

For Mel, ordination was the crucial event of his life. At the very end of his life, he was writing his autobiography. I don't know how far he got, but he told me that the autobiography started with his ordination. And then he was gonna tell about his life up through ordination and then tell about his life after ordination.

When I was at Tassajara, a novice priest was there. Mel was directing the practice period with Steve Stuckey. And this novice priest said, his teacher had said, "Just watch Mel." That Mel was the epitome of a Zen priest. And so he watched Mel and it was great. But the thing about that is that Mel himself said, "I'm bad at ceremonies." And from the outside, you could say he was, he forgot where he was supposed to bow and where he was supposed to walk. And people would say, "Go that way." But it was wonderful because his presence was extraordinary because it was so ordinary. He just went up to the altar. He just bowed. It was amazing.

This was crucial for Mel. And if you look at it, he was ordained. Ordained actually comes from the Latin word ordinationem, which means "setting in order." And it's related to ordinary. The root is ordo, which means setting in a row or arranging something. So ordination, the very word epitomizes Mel just to be ordinary.

Ordination is setting an order or at least a vow to work on setting yourself in order. We usually think of ordinary as kind of a little boring, a little pedestrian. And we contrast it to extraordinary or special. And if you look at Mel's Dharma name Sojun, essence of purity, both of those sound pretty damn special. I don't know of anyone who could really say they feel they're pure, let alone the essence of purity. It's kind of weird. Purity would imply cleanliness. And Mel is a real earthy guy. He loves to work in the garden. "I get real dirty with the earth." He loves that.

So what was Suzuki Roshi thinking? Essence, the root of essence is esse, which means "to be" in Latin. So it's the most basic thing in any language, the verb to be. So it's the isness of all of us and of everything. This rock is, this priest is, this priest is the essence of purity. And as I said, you wouldn't end being a priest disorder. And that's the essence of being a priest, maybe. So much too early priest to say what the essence of being a priest is, but that's where it comes from, setting an order, being ordinary.

My first sense of what is the essence of purity and what this could conceivably mean came from watching Mel make tea. So I'll tell you about my practice with Mel. And for now, the beginning of my practice with Mel.

When I came to practice at Berkeley Zen Center, Mel had been leading it for about 30 years. So it was very Mel. And so here's the story. It was the first and only time I took a plane up to the bay and then a cab. And we went to where the address that had been given. And there were a bunch of houses. There was no Zen center inside. There's just a bunch of ordinary houses. And so the cab and I both started looking. We looked maybe for 10 minutes and couldn't find a Zen center. And so then we checked the address. The address was right. We looked some more. And finally, there was this ordinary looking place and there was a big shrub in front of the gate. And behind the big shrub hidden was a very small sign that said Zen center. So I paid the cabbie and I walked through the gate. And that feels like Mel's first teaching for me, even though I hadn't even entered his temple at that point.

At this sesshin, I did my first dokusan with Mel. And Berkeley Zen Center has a lovely little hut, dokusan hut. So I went up the three stairs or so and took off my sandals and then I got the form wrong. I think I sort of started to open the door before he had rung the bell. So Mel corrected me. And then I went in and I bowed and then I sat in front of him. And I had been kind of primed for this by Alan Senauke who is now the abbot of Berkeley Zen Center. And we had practice discussions with senior people. So Alan said, "Why don't you ask him what shikantaza is?" And I said, "Okay, I'll ask him what shikantaza is." So I did my bows and faced Mel and said, "What is shikantaza?"

And for the life of me, I cannot remember anything I said or he said for the next 15 minutes or so, nothing. All I know is that when I got out, I was just flooded with the thought, I met a Buddha. I met a Buddha, I met a Buddha. And all through the rest of that session, as I said, there were practice discussions with senior people. And each practice discussion, I'd show up and I said, I met a Buddha, I met a Buddha. And Alan said, sounds like a good day. So that was how it started. How my practice with Mel started. And it was wonderful. And he kind of became more and more ordinary all the time. And the more ordinary he was, the more we were kind of in awe of him. It was amazing.

So after maybe 10 or 15 years, I started chamber music with Mel. The way to Mel's heart is to be able to play a musical instrument well enough to play chamber music with him. So he played the recorder and I played the piano and we would warm up and then play Bach for hours. And I think I can say we both loved it. It was fantastic. And it was weird because one thing that happened as we were playing Bach was that we both made some mistakes. Like we played a rhythm wrong or skipped a beat or something. And so when Mel played a rhythm wrong or skipped a beat, after a while I would say, hey Mel, try this. And so after a while I was just teaching Mel music and it was very natural. It felt so ordinary. So I was teaching Mel music and he was teaching me Zen and it was so pure. It was just nothing, it neither interfered with the other at all. They were just both happening. And so it was great.

And Mel was a really good music student. He would listen to what I said and try it and work on it a bit and then he would get it right. And if he didn't understand what I was trying to say, he'd ask and I'd respond and he would then understand it and work on it and get it right. So he was a really good music student. The only problem with Mel as a music student was that he never practiced. And I personally think he had a really good excuse. I mean, he was saving sentient beings and he was in his 80s, so good excuse. But so once I teased him about it, I said, hey Mel, you're always going on about practice enlightenment. Why don't you practice the recorder? And he laughed and laughed, he loved it.

And so sometimes Mel would make tea or lunch for me and he'd never let me help him. Maybe one time in all those years. And so I took that as a big opportunity for teaching which it super was. Actually, I guess since Mel died, I told my friend Jury who I'd love to get down, she's a teacher at BCC. And she said, well, Mel is very fussy and wants everything to do precisely. And it might not have been this big teaching thing in his mind, it might've been, oh God, well, let me do it myself because, but I took it as a big teaching thing. And that's maybe where I learned the most, watching him make tea, watching him chop vegetables.

And I was thinking about Mel's description of him working with Suzuki Roshi, that Mel would just watch everything Suzuki Roshi did, like intensely and wonder what kind of mind is behind Suzuki Roshi doing these actions. So I watched Mel chopping vegetables and making tea very intensely, as much concentration as I could muster. And at first it looked like anyone else just chopping vegetables and making tea. There's nothing special about it, it was very ordinary. But as I kept watching, there was a kind of quiet presence about it. It's like Mel would pick up the kettle. He would just pick up the kettle and he just moved to the sink. And he would just hold the kettle under the faucet and open the lid. And then he would just turn on the water. And then he would turn off the water. And then he would take the kettle and put it on a burner. And then he would light the burner. And all of this was done as very ordinary. There was no fuss about it. It was just what he was doing, but he was there with what he was doing. Very peaceful. Very much this moment, pick up kettle. This moment and picking up kettle are the same thing. There's no fuss. That's it, ordinary.

And sometimes things went wrong. So it was ordinary. Something falls on the floor. Now I just pick it up. That's all. There's no problem. This is just the next moment, the next thing to do. And so Mel did it and didn't comment on it. And after a while, well, of course I sort of tried to do, you know, to emulate Mel in doing things like this. It was, I guess, fairly okay. On Mel watch, didn't say anything. And then he said, you know, when you finish something, you are beginning to think about the next step. And then I said, yeah, Mel, you're right. That's what's happening. And so I worked on noticing that and just not doing it. When I noticed I would stop. And that made that purity, again, purity of that moment much more real for me. So I made tea with Mel or rather I watched Mel make tea. And it just was very ordinary and really amazing.

So there's an absolutely wonderful Zen story about ordinary, being ordinary, ordinary mind. And we can look at it a little bit. We don't have much time, but here it is. It concerns Nanquan, a very great teacher in Tang Dynasty China and this kid named Zhaozhou. And Zhaozhou was about 18 years old and he just arrived at the monastery. So he asked his teacher, what is the way? And, you know, I was talking to Bill and trying to get Bill to tell us because he's amazing. We got to get Bill to talk about the way. But not wanting to bother Bill too much, I consulted a great authority, namely Google, which said that the Tao is the absolute principle underlying the universe, signifying the way that is in harmony with the natural order. But the Tao is actually bigger than that. It's bigger than, you know, you can't complete the sentence.

And Google is up against a big problem because the first line of the concept Tao originates, I think, with this wonderful thing, the Tao Te Ching. And the first line of the Tao Te Ching is the Tao that can be told is not the true Tao. So anything you say about the Tao is a lie in a sense. So when Buddhism came to China, it was very influenced by Taoism, particularly I think Zen. And so we have the expression the Buddha Way or Butsudo in Japanese.

So Zhaozhou asked, what is the way? And maybe he was maybe just got there as what is the way at this monastery? And it was a very famous monastery. So he probably thought that they do real special stuff here. But his teacher said that ordinary mind is the way. And I imagine Zhaozhou must have been astonished. His teacher was summing up the whole teachings of the Buddha, the whole universe. And what all of that was, the word that applied to that is ordinary.

So Zhaozhou said, shall I direct myself toward it? But if you think adding emphasis, shall I direct myself towards it? So the idea of directing himself towards it was setting up a dualism. Here's Zhaozhou and here's the way. But if the way is as big a deal as the Tao Te Ching seems to be saying, everything is the way. I mean, we're stuck with it. I mean, we're enmeshed in the way we are not separate. That's the way. So Zhaozhou didn't get it. So how could Zhaozhou be separate from the way? It's impossible.

So Nanquan said, if you direct yourself towards it, you will move away from it. So the ordinary mind is just what's here right now, this moment, this moment, this moment. So if you try to go anywhere, of course you're going away from it. I mean, it's impossible to go away from it. We're stuck in it.

So Zhaozhou said, if I don't try, how will I know the way? And this is where it's like the Tao that is the true Tao cannot be spoken. He's concerned that if he doesn't try, he's not gonna know the way. But I guess he wants to be sure that, oh, now I know the way. And he wants to be sure that if he gets a wrong idea about the way, he'll know that's not it. But again, this is implying that he's separate from the way and nothing is separate from the way. There's no knower who could know the way outside of the way.

So Nanquan went on, the way is not concerned with knowing or not knowing. And he goes on, knowing is illusion. Not knowing is blind consciousness. If you truly arrive at the great way of no trying, it will be like great emptiness, vast and clear. How can we speak of it in terms of affirming or negating?

So the great way of no trying, Suzuki Roshi, I think somewhere said that there's effort, but we lose ourselves in the effort that we make. And losing yourself, it's really, it's like the Tao, you can't speak of it. I think of it maybe as Dogen's expression, dropping off body and mind. And there's no speaking of it. I mean, it's neat because all the teachers commenting, I mean, I saw Eiken Roshi and Dido Loori and Wu Men himself who compiled the Wu Men Kuan where you'll find this koan. They just complain, they say, Nanquan talked too much. He should have just let Zhaozhou figure it out himself. But I think my feeling based on trying to figure this out and what to say is that they just gave up. And he just said, you can't talk about it. Nanquan shouldn't have even tried.

So the next thing that happens is the end of the koan. Joshua immediately realized the profound teaching. Fortunately, Joshua didn't let it go to his head. He stayed at Nansen's monastery for 30 years until his teacher died. Then he went on a 20-year pilgrimage to deepen his understanding. He said if there was a little child who could teach him, he wanted to meet that child. And if he could help anyone and teach them, he wanted to help them and teach them.

When he was 80, he settled down and started teaching at a monastery. He lived until he was 120. So he really beat Mel at that one. He was one of the great, great masters and the most famous story about him is the koan Mu. "Does the dog have a Buddha nature?" "Mu," no. That's the most famous, but there are many wonderful koans about Joshu.

Let's see, where does it happen to this stuff? So, let me finish with Mel, if I can find him. Someone here. Oh, one thing, as I'm looking for, is that teachers have teaching words. Like people say, when Suzuki Roshi said, "Just sit." Mel's teaching word was "okay." He didn't say "ordinary" very much, he just was ordinary. But if you ask Mel about anything, like how he was, he'd just say, "okay."

And then one time, finally, someone said, "Mel, I mean, aren't there days which are horrible and everything goes wrong and you feel miserable?" And he said, "Sure, they're wrong, that's okay." And so, okay, I was joking with a real senior priest and we were saying, well, there's gonna be Master Sojun's "okay" is gonna be one of those teaching words. One thing, and I understand that as, you lift the kettle, okay. Kettle falls on the floor, okay. All sorts of water spills on the floor, okay. Mop up the floor, okay.

One thing of Suzuki Roshi and then Mel. Suzuki Roshi said, "By purity, we mean things as they are." So, I'll leave the last word to Sojun Roshi, essence of purity, my friend Mel:

"The doorway of enlightenment, the gateless gate is open right in front of us, but it's so obvious and ordinary that it is only visible to the selfless. The selfless see the extraordinary quality of life in the dharmas of our ordinary world. And others suffer trying to be special while missing the special qualities of their ordinariness. The way is practice, and practice is not stagnating, but rather living each moment fully, one moment at a time, without creating too much difficult karma, offering ourselves unselfishly to the support of other beings while we walk freely, while we walk freely through the opening gate."

So, thank you very much. Any comments, questions?