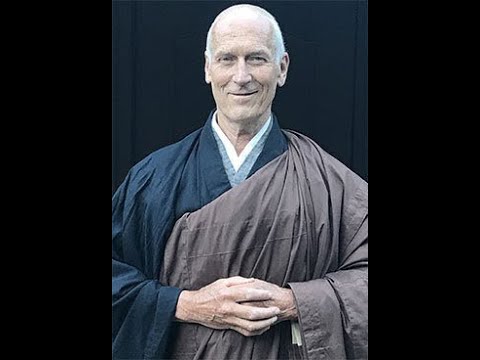

Kaizan Doug Jacobson — The Timelessness of Awareness

Kaizan Doug Jacobson began practicing Zen in 1974 with Dainin Katagiri Roshi in Minneapolis; he had Jukai in 1977. A householder, father, contractor, and civil/tunnel engineer, following his retirement, he became a full-time resident at Jikoji Zen Center near Los Gatos. He received priest ordination in 2010 and Dharma transmission from Shoho Michael Newhall in 2015. He has led many sesshins, monthly zazenkais, periodic seasonal nature sesshins, and weekly dharma discussion groups. He also helps to maintain and develop infrastructure at Jikoji, getting his hands dirty as a form of Zen practice. In addition, he assists prisoners with Buddhist practice.

Full Transcript

Good morning everyone. Glad to be back here with all of you. Grateful too. Today, momentarily, I think is the beginning of spring. Today, we're going to do a spring ceremony here at Jikoji. Gerow Reiss has years ago made these large boards, each with an inscription of the season in English. They're on four by eight foot sheets of fine birch plywood. We're going to do a ceremony of transporting spring to its new location below the courtyard where Hogan has put a mounting place. We'll have clappers and bells. Mike was hoping for young maidens tossing flower petals. I don't think that's going to happen, but maybe some old men can toss some petals.

Today, I wanted to speak about, I guess, what we do and what this is all about a little. Suzuki Roshi once said, a person who falls on the earth stumbling on a stone will stand up by means of the same earth they fell on. You complain because you think the earth and the stone are the problem, having caused your fall. Without the earth, you wouldn't fall, but you wouldn't stand up either. Fall and stand, falling and standing up are both great aids given to you by the earth because of mother earth you can continue your practice. You are practicing in the zendo, on the zendo of the great earth, which is your problem, all of our problem. And problems are actually our zendo.

So speaking of earth, to extend that metaphor a little more, there are many kinds of ways we interact with the earth, and there are numerous ways of how it affects us. And what I'd like to do is, I think I've spoken of this before on some of the many kinds of friction there are, usually describing how particles interact with each other, but some of these are wonderful descriptors of how we interact with each other. Adhesion, cohesion, atomic attraction, molecular attraction, valence bonding, sliding friction, rolling friction, interlocking friction, crushing friction, dilation, geometric interference, particle pushing, stick slip, bonded, lubricated, elastic and plastic and viscous. These are some of the descriptors for friction and the forces between particles.

And I was just on a trip to Los Angeles and to northwestern Arizona, south of Lake Mead, where I visited some of my friends. And in visiting my friends, they described another force of a very clay road that they, when it's wet, the clay road is greasy. And sometimes, you know, grease is a lubrication, but it's also a stickiness. And when they drive this road, when the clay soil is greasy, the greasiness gets embedded in the knobs of the tires and between the dual rear tires and stuck to the bottom of their RV. And it's just a real hassle to deal with that greasy situation. So they avoid traveling to that location when it's greasy. The other condition that happens on that road is dusty. And when the greasy clay dries and it gets pulverized, the particles break apart quite easily and get airborne by the vigor of vehicles passing by. So it's just interesting that one kind of mineral, a clay, clay minerals, are able to both be greasy as well as airborne and atomized almost.

So I'd like to apply this a little bit to our experience as well. And Ruth King, who is a Buddhist teacher, she writes that Buddhism teaches us to pay attention to the reinforcing mechanisms of misperceiving ways we have been mentally conditioned to distort reality. And this mechanism consists of a three-part cycle. We perceive through our senses, the eyes see, the ears hear, the nose smells, the body touches, the tongue tastes, and the mind thinks. The second part of the three-part cycle is once we perceive, the mind habitually jumps to thoughts and feelings about what has been perceived, commonly rooted in past experiences and conditioning. Thoughts and feelings then influence the mood of our mind. And when perceptions, thoughts, and feelings are reinforced, then the third part of this cycle happens. Our views and beliefs solidify. They stay intact as truth, flavoring how we experience and respond to the next moment in the world.

So we perceive, our mind then jumps to the thoughts and feelings about what has been perceived and then roots it in past experiences and conditioning, and gets sticky with these influences of preconditioned thought and further reinforces our views and they solidify. And we consider them as truth, flavoring this experience.

Toni Morrison, who many of you know, a writer and recently deceased, great author, wrote I know the world is bruised and bleeding and though it is important not to ignore its pain, it is also critical to refuse to succumb to its malevolence. Like failure, chaos contains information that can lead to knowledge and even wisdom and even art. And art reminds us that we belong here and if we serve, we last. It's critical to the understanding of what it means to care deeply and to be human completely.

So what I appreciate about what Toni Morrison said is that it's important not to ignore the pain, but she goes on to say that we should not succumb to the malevolence that also arises. And that's where practice really begins to do its work.

You know our existence has such bounty each moment. Our sixth sense organs, the six sense objects, the myriad sense objects that we can't experience and then our six consciousnesses make sense out of it. And these all exist in the realm of the relative. And we can point to each of these six senses and we can point to each of these six senses as independent things and we mix, we can even mix these up.

When going to a classical concert, often people go to when you hear a string quartet or an orchestra play, there's motion there, there's great sound and many people close their eyes so they can really experience the sound. However, there's sound to experience in the body and there's the vitality of the performance that can be experienced with our eyes. Some of you may have seen the Kronos quartet and one of the passages in their performances, the rosin on their bow, this material rosin coming from tree pitch sticks to the bow and causes friction between the bow and the string and they load up the bows with rosin and then swish their bows through the air, releasing the rosin dust into the air. And so with your eyes closed, how do you experience that? Maybe with your nose if you're close enough to smell the rosin, but we get all of the sensory inputs coming in that result in a dynamic experience and all these exist in time and space.

We can touch each of our sense organs, we can touch our eyes, our ears, our nose, our tongue, this body, I don't know how we exactly touch our mind, which brings me to a recent experience. Just a couple of days ago, I was holding my six-week-old granddaughter with her head in my hand and her bottom and legs in my other hand against my body and to hold this entire package within two hands is just so sweet and inconceivable, inconceivable that this thing that has fingers slightly bigger than the size of toothpicks will one day be like us.

Now, what I'd like to have us next attempt to touch is our awareness. Where does our awareness reside? Is there a place, is there a space where awareness resides? Does awareness even have a place or is it even contained in space? Is awareness, our immediate awareness exists in time or can awareness only be now? And our thinking brings us to the relative, to the past, to the future, to past spaces in time, to future potential spaces in time. So I would like to assert that our awareness exists in spacelessness and timelessness, and actually our pure awareness is our direct connection to eternity. So that's my assertion I would like to offer up for discussion.

And I would like to close with another quote from Suzuki Roshi, where he says, in our life, there is really no time, no place, and no space. If you live your life by doing everything with your whole body, then you are in that condition of no time, no place, no space. There isn't even an opening big enough for passions, desires, or enlightenment to enter. A person like this is truly free, a Buddha. So thank you.