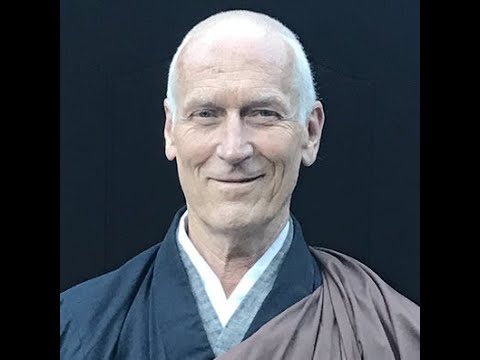

Shoho Michael Newhall — What Remains: The Simplicity of Zen Practice

Shoho Michael Newhall began practicing and studying with Kobun Chino Otogawa Roshi in the early seventies, and was ordained by Kobun in the mid-eighties. In the early nineties he became director at Jikoji Zen Center. Throughout this time he taught art and Buddhism at Naropa University, the Art Institute of Chicago, and other universities in the midwest. Mike has led sesshins and meditation workshops at Zen centers in the U.S. and Europe. Shoho has also practiced and studied with Keibun Otogawa in Japan, Dainin Katagiri Roshi, and Tenshin Reb Anderson. Mike lives at Jikoji, serving as the Resident Teacher and Chief Priest.

Full Transcript

Can you hear me? Everyone can hear me. Yes. Okay. Well, good morning. Good morning Santa Barbara. I'm honored to be with you again. I remember well the Sangha down there when I visited some time ago, and it's very nice to connect again with you. Thank you for inviting me to join you.

We are hopefully coming out of a challenging year. And I thought we could talk together about the simplicity and the economy of this practice way. So this morning, let's begin typically with a Zen story. This is like most Zen stories. This is a conversation between Xiao Zhou, who became a very famous teacher. There are many stories about Xiao Zhou and as a younger monk at that time, he approached his teacher, Nan Juan. You may be familiar with the Japanese translations. Xiao Zhou in Japanese is Joshu and Nan Juan is Nansen.

So Xiao Zhou came to Nansen and he said, "What is the way?" Nan Juan said, "Ordinary mind is the way" or "mind, just as it is," or "everyday mind." Xiao Zhou said, "Shall I try for this? Shall I turn toward this?" Nan Juan said, "Well, if you do so, you'll be separated from it. You'll miss it." Xiao Zhou said, "How can I know the way unless I try for it?" Nan Juan said, "The way is not knowing and it's not not knowing. It's neither knowing nor not knowing. Find that place." Nan Juan said, "Find that place that is neither knowing nor not knowing. This is neither trying or not trying. And you will find vastness itself." For Xiao Zhou, this was a turning point. He realized something and continued his practice.

We often think in our practice way of a goal or at least a direction, or have an aspiration or make an effort. And this teaching conveys to us a kind of cautionary warning to not employ the kind of merchant's mind that sometimes arises in us, commonly arises in us. I have to say this. A merchant's mind is a mind that has a kind of bargaining mind that says, if I do this, then I will get this. If I try to have an ordinary mind, an unfabricated mind, a natural mind, I'm going to try for that. And Nansen says, don't try, but find that place that is neither trying nor not trying. Find that middle, that mean, that middle path that is neither trying nor not trying and enter there.

So this is how I'd like to approach a sense of how we can enjoy and meet this unfabricated, this unembellished, this ordinary, this just as it is kind of existence without the ideas and the conceptualization of putting on extra clothing, putting on the embellishment of being something special or being something unique or being a Zen student, just being yourself.

In the early Sangha, the term for someone who was recognized or understood to have kind of negotiated the way, was called an Arhat. And an Arhat was someone who put aside what was called the asravas. An asrava is a Sanskrit term that means it has some different translations. An asrava sometimes gets translated as leaking. So an Arhat, someone who has negotiated the way, has put aside leaking. He has stopped leaking. The other translations of an asrava is effluent. There's even this connotation of it's kind of like a sword that's leaking.

Someone who's an Arhat has put aside the leaking of being anything, being on as an identity. It's called a bhava asrava, the asrava of the leaking or the loss of energy or the diminishment of one's essential being has been diminished. As you leak that, put aside that the asrava, the bhava asrava of wanting to be something, wanting to be, even be an Arhat, be anything. It's gone. It stopped leaking of that. And put aside what's called dithasrava. And dithasrava is the leaking or the diminishment or the loss of energy that comes from having a view, having a fixed view, having conceptualized or reified the ungraspability of life. Try to hold it with a view, with conceptual imputation.

I think Dan mentioned about a sangha, who at the right before the first council in a talk here a couple of weeks ago, mentioned someone who had finally, before the first council had put aside this leaking. So this is kind of an understanding of how the early sangha understood the way. It was not accumulation. It was not acquiring specialness, it's not acquiring any special powers. It was releasing. It was letting go. It was dissolving.

I heard one teacher say about Asravas that there's two kinds of this leaking. You can leak by like a bucket that has a leak in the bottom of it and your energy, your vitality, your presence is diminished by kind of leaking out of the bottom. So we can imagine someone who maybe lacks confidence or energy to practice would kind of leak out of the bottom of their practice. There's another kind of leaking this teacher said, it's kind of leaking over the top. You kind of flood your presence or your environment by being too full. So you leak over the top. You kind of flood your environment. Maybe you have a big idea. You're a very important person and you've practiced a little while and you think you're a big deal. And you flood your environment and leak over the top.

So this is one understanding in the early Sangha of the way was not accumulation, not acquiring special attributes of any kind, but letting things go, letting things dissolve and then seeing what's left, what remains. And that's the question for us. We drop off body and mind, as Dogen said, when we practice. We try to release our constant conceptual imputations and our fabrications of what we are and what the world is and just sit with our body and mind when we practice. And of course, we notice an internal dialogue sometimes and our thoughts carry us away. That's kind of the momentum of our just what our minds do. But as we practice, as we continue to practice, we find that conceptual imputation, that fabrication, that you could say our mental creativity, our fashioning of the world starts to dissolve or get softer. In other words, we release, we let go. We stop leaking in this way or we at least suspend the leaking of our existence.

The early sangha made a point of being, of really simplifying their lives. So the early monks and nuns, those who decided to take on this practice wholeheartedly, as you might say, as a full-time job, they left the householder life. They left their ordinary life and chose to lead a radically simple life. So they just had no possessions. They had a robe and a bowl. They kept things very, very simple. And they just received food. They didn't even work. They focused entirely on meditation and practice. So it was a kind of radical simplicity. That simplicity, that outward simplicity was actually not the point. The point was that internally, within themselves, in their minds, in their internal work, that's essentially what they were simplifying. And the outward expression of just having a robe and a bowl, that was just the outward expression of what they were doing internally. They were making things simple and direct. They were taking things off. They were not acquiring things.

It's even said that the monks that had practiced for a long time, they had bowls, and they would receive food from the laity. And they would come to the laity's house and ask for an offering. And it said that the older monks who had practiced longer and had become more empty, become more simple, become more elemental. They received more food because their bowls appeared to be more empty. The younger monks, who still had ideas and conceptualizations, they didn't get as much food because their bowls, same kind of bowls, but their bowls appeared to the laity on some intuitive level, to be less empty. So they got less food.

So this is kind of an understanding of how the early sangha, you could say, practiced a kind of deconstruction or a reductive sense rather than an accumulative sense. There's another interesting term called avarana. And avarana means, this is a Sanskrit term also, and it means a veil or a covering or an obscuration. So this was in the early sangha as well. So the monks and the nuns in practicing practiced releasing what's called kamasrava. And kamasrava means the veil or the obscuration due to desire or attachment or thirst. Or bhavasrava, it's kind of this similar term to the avarana of becoming or identification. And these all have negative aspects too.

As well as putting aside the desire for becoming or identification or fabricating an identity or a self, you know, sort of building a self. There's a negative aspect to the bhavasrava, which is the desire for negation, the desire to disappear, the desire to escape. So the early monks put aside bhavasrava, the obscuration of becoming or not becoming. They put aside both. They put aside the attachment, the attachment and desire and thirst of kamasrava. Or the negative part of that, which is aversion, hatred. They put aside the desire for it and then you could say the resistance toward it as well. And they put aside dithasrava, the desire to have a view or to have a fixed identification with a particular opinion or even a ritual or anything like that. They put aside that. They let that go. They released it.

And even there's another one that's even more subtle. It's called ajiva asrava. And that's the veil of ignorance itself. In other words, the indulgence you could say of not wanting to know, but just avoiding knowing. The situation here is as you can see, there's not an accumulation of any kind of attribute, as I said before. It's putting aside these things, letting this go, letting that go, letting the views go, letting the emotions go, letting these habits go. And then we can ask ourselves, we can inquire, okay, I put aside this attachment to this view. What's left? What remains? Or where am I now?

And it may be more familiar to you. We have these three kleshas. Sometimes translated as greed, anger, and ignorance, or attachment, aversion, and delusion. The three poisons are the three kleshas they're called. Klesha means to stain. Something was pure and became stained, became discolored. So we have that in Buddhism. And we also have something called the five hindrances. What are they now? The five hindrances are sense desires, ill will, restlessness, and worry. Another one that I can relate to is called sloth and torpor. I love that one. And the fifth one is called doubt, or sometimes translated as hesitation or vacillation.

So what's interesting, as you can see in early Buddhism, in foundational Buddhism, they're not talking about so much about any kind of special state or transcendent experience. What early Buddhism or foundational Buddhism seems to be attending to is noticing what we need to release ourselves from, what we need to put away from, what we need to put away. And then whatever remains, having put away sloth and torpor, for instance, what remains? What remains for me? If I'm slothful or torpor means sloth, sloth means not even beginning. Torpor means kind of just loss of energy. Having put away those attributes, then I can say to myself, okay, Michael, I put away sloth and torpor. What remains? Well, maybe some energy. Maybe a kind of relationship to the world that doesn't have that attribute.

Having put aside these clinging, these attachments, these grasping to certain sensual desires, say my desire for a certain kind of food or a desire for recognition for another person, wanting the approval of another person. So I've examined that in myself. And I've looked at that asura or that klesha or that hindrance, however you want to put it. I've looked at that, I've examined it, I've practiced with it, I've recognized it in myself, and I've released it. I've let it go. I've let it go by accepting myself. I've let it go by not giving it attention. What remains? What's left? Well, we could say a life without that clinging, a life that's liberated, that's released, that my life is not fabricated or embellished or contained by that attention or interest or obsession with wanting the approval of this other person. I'm liberated, I'm released from that.

So the teaching that we're receiving from this early sangha is we do not have to ask ourselves what we can get from our practice, what special state we can arrive at, whether it's just to be more peaceful or to have special knowledge or to be more aware or to have special knowledge or to have a better relationship with things, we don't have to have a sense of trying to acquire that. This understanding from these early teachings is we don't necessarily have to move toward a specific goal like that. We can actually relax from that acquisition mentality, that merchant's mind of trying to acquire a special state. What we can do is let go of these, let go and simplify our practice by bringing in releasing ourselves from these kleshas, from these hindrances.

So Xiao Zhou, you know, he was a young monk and he wanted to get something. And he asked his teacher, he asked this Nansen, "Hey, shall I try for that? Shall I try for this, this unfabricated mind, this pure mind?" And Nansen said, "Don't try, don't try, don't try to know it. Find that place that's neither knowing or not knowing and enter there."

So the question comes up for us. We sit in meditation. This is our work, this is our activity. We do meditation, we do something very, very simple. We just sit down, we find that, we kind of make an intentional situation where we sit down and we're very quiet, we're very still. And we see, we meet our body and mind just as it is. And we notice that within our body and mind, there arises, whatever arises in our body and mind, we try and meet without embellishment as simply as possible. And to put aside, put aside these kleshas and see what remains, see what's left.

And we could say, what's left is nothing special. It's just our life. It's just our life as it is. It's not a transcendental state, or maybe it is a transcendental state, but it need not be a transcendental state. It could just be, it could just be a cup of coffee. It could be washing the dishes. It could be, as Nansen said, it could be ordinary mind. It could be everyday mind. What is the way, Xiao Zhou said, and Nansen said, your ordinary mind, your mind just as it is, unfabricated, that's the way.