Pamela Nenzen Brown — Birthing and Deathing: Embracing Life's Transience

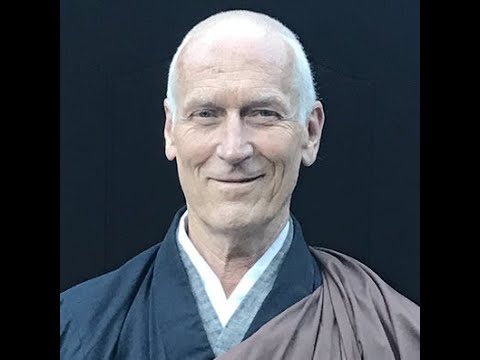

In 2017, Pamela met Sensei Gary Koan Janka and has been sitting with Santa Barbara Zen Center ever since. Koan Sensei introduced Pamela and SBZC to Jikoji Zen Center, Pamela was ordained in Kobun Chino Ottogawa Roshi's lineage by Shoho Michael Newhall in 2020. She received dharma transmission from Jakko Eso Vanja Palmers at Felsentor, Switzerland in 2022.

Full Transcript

Tata on opening the sutra. The diamond, incredibly profound and infinitely subtle, is rarely encountered, even in a billion of the seven reaches. And when we see it, hear it, receive it, and maintain it, may we completely realize that our guidance is teaching.

Good morning, Sangha. Good morning. Near and not so near, but near. So I see some new faces, and I'd like to go around the room if we could please, and introduce ourselves. Michael. Rob. No. Chris. Logan. Yarny. Steven. Steven. Tom. Tom. Paul. Steven. Michael. Dave. And I'm Nenzen, or Pamela, or Payu.

So I've just returned from a week at Jikoji at sesshin. Sesshin is, for those of you who have not surrendered to this yet. Okay, tell me, Paul, tell me if I'm not loud enough, okay? Thank you. I've just returned from a week at sesshin, which is an extended retreat. I don't know why they call them retreats. I always think it's in advance. But you sit basically from quite early in the morning in silence, noble silence, which means only speaking when it's absolutely necessary, and you just go in and go in and go in. From early in the morning until evening, where you sing the refuges and you go to bed. All the meals are orioki. Everything is in silence.

And the first few days, there were some people from Santa Barbara Zen Center who came this time. And the first few days are reliably difficult for everyone. Even those of us who've done it a lot, there's this little mountain you have to climb of resistance, like, what am I doing? Why am I doing this again? It doesn't work. Why am I doing this again? It doesn't matter if you've done it a million times and you know what the process is. There's still this little resistance.

As we were walking outside this morning, I hope some of you noticed the cast shadows that you were all creating, these beautiful long cast shadows. And then you walked into the little dappled sunlight and then the shade. And then our fearless leader takes us onto the grass. Off road into touching the earth in a very real way. And back in cast shadows and dappled light. And like sesshin, really, this is that process, looking at shadows while you're sitting, trying to see what you're not seeing as you sit there.

After a few days, you start noticing. So all week sitting, I was paying attention deeply to each moment, birthing and deathing, birth and death, birth and death, birthing and deathing. Creating this self. Creating the self going by. And then the next self. And then the next self. And asking myself to look in the shadow. What is the ball of iron in my throat? What is breaking my heart? Right now. Right now. Right now.

And as is often happens at sesshin after a couple of days of this now, now, now, I fell again in love with life. Life. In all its glory. In all its confusion. And messiness. And perfect imperfection. Which is to say that I fell in love with the discomfort in this life, my life. With the discomfort of my suffering. And kind of the discomfort of joy, too. I fell in love with life's complexities. The way I'm always trying to balance everything that's coming. The way I often feel like I'm putting out fires. Got that handled, got that handled, got that handled, check, check, check. But in fact at sesshin you start to notice that there's no fires, there's nothing to put out. You're just burning through. Just burning through everything. And that's a better way to burn through it all. To let it burn.

Anyway, I recognized the things that I call suffering. As in having inherent in them this great joy of being alive. Just simply being alive. Almost like the divinity of each moment has to have everything. There's kind of a magic of just being alive. Nothing more. I just kept keeping my heart open. We talk a lot about having an open-hearted practice. At sesshin you have uninterrupted time to open and open. Because there are no distractions. They've taken care of your food. They've taken care of your bed. They've taken care of the clock with all the bells and the hawn. They've taken care of everything. All you have to do is sit down and be quiet.

So in this open-hearted practice I admitted kind of the pristiness of my own heart. And yours. And everyone's. Right in the middle of suffering. And grief. And loss. And joy. So I guess I fell in love with kind of the exquisite heartbreak. Being human. And I allowed and I would dare say I accepted the pain of this heartbreak. I completely accepted the pain of my heartbreak. With this kind of joy. I don't know how to explain that but that's how it felt.

I saw that this mind that arose of acceptance of the whole beautiful catastrophe, as our friend Joel likes to say. That that awareness has to do with an awareness of transience. A deep awareness. That everything is moving. In Shobu Genzo which is Dogen Zenji's beautiful treatise. Dogen Zenji is the founder of Soto Zen which is which we are a part. He has Shuke Kudoku which is Merits of the Monastic's Life. It's a little treatise in Shobu Genzo which is a collection. He notes that most people do not understand this mind of awareness of transience. Unless they can take in deeply the understanding that a day consists of 6,400,099,180 moments. That was his number. I don't know where he got it. If you look in a Buddhist dictionary instead of that number they say that one moment equals 175th of a second. The numbers don't really matter. They're just placeholders like we're placeholders.

The important part to remember is that from moment to moment this life goes quickly by. Birthing, deathing. Maybe in your city you have noticed how temporary your experiences are. Your mental states, the self that arises. You see them come, you see them go, you see them gone, you see them go. You don't have the same feelings about some things that you had a week ago. Much less a minute ago. It's just moving, moving, moving. It's a good reminder of how temporary we are. It's important. That you know how temporary we are. We and everything else appear and disappear in a moment.

It's like when you wake up from sleep and sometimes in those first few moments, I don't know if you have this experience. I assume everybody has my experiences because I look out of these eyeballs. So tell me, raise your hand if you've had this experience. You wake up and you're like, oh, I'm going to die. You wake up and you're not sure who you are or where you are. And you feel yourself, yeah. Familiar, right? All of you. You feel yourself starting to reassemble, right? You start to see the little pieces, okay. Here I am. And who is I? Oh, yeah, I remember who I am. Like that, moment to moment. Moment to moment. You slowly watch yourself reassemble. Birth and death, that awareness is actually the functioning of each of those bazillion moments. Now you see it. Now you don't. Like that.

You know, this sounds disturbing, right? Because there's nothing that you can hang on to. But it is also a great comfort. If you can allow yourself to go towards that feeling of disturbance, you might also see great comfort. Because whatever is arising, no matter what it is, it's moving. It's not staying. It's going to go. So what's difficult, we can face even as it's unfolding. Because you know it will not remain like this. So it's best not to cling to the highs or cling to the lows and identify with them. Because it's temporary. Like us.

So one way to express this awareness of transience came from our friend Gerow. Some of you know Gerow. He's a wise guy. He's a wise guy. What he likes to say is that everything is a gerund. A gerund is the ing ending. So this is Mariko Ing. This is Dave Ing. This is Juliana Ing and Paul Ing and Kovac and Steve Ing. It goes on and on and on and on. This is Nenzen Ing. Because I'm not any fixed idea that you might have about me or that I might want about me or not like about me. It's moving.

We were up at Jikoji celebrating Tanjou. That was the name of this scene. Tanjou is a celebration of Buddha's birthday. And you know there's a whole ritual and ceremony. You bathe a little baby Buddha. And it's kind of fun. Sometimes there are kids. We had one kid. Thank goodness. And I always remember on Buddha's birthday the line from the Oroyoke chant. Buddha was born in, anybody remember it? Lumbini. So that first line, Buddha was born in Lumbini always strikes me because what's not in the chant is six days after Buddha was born in Lumbini, his mother died.

So Buddha's mother, her name was Maha Maya, Maha, great. I'm sorry, Maha Maya. Great Maha. Maya was her name. She died. And he was raised, Siddhartha was raised by his aunt. This is Maya's sister whose name was Pajapati. We call her Maha Pajapati. So you know her name from our chant. Maha Pajapati, the first woman ancestor.

So I've always considered this co-arising. This birth of Buddha's where he's going to be the awakened one and he knows it right away. He stands up and says, this birth of Buddha's coincides with this incredible psychic wound, the loss of his mother. I think it's remarkable that in all of the lifetimes, the prior lifetimes of this Buddha, it's this one in which he suffers this psychic loss in which he is going to be awakened. He has to integrate this profound loss in order to be awakened.

We're doing that too. Loss is part of being human. And it is a way that we measure time. Who we were before this loss, everything that followed after this loss. We use it like a timepiece. It marks our lives. We measure things before and after. And the losses, they come. They keep coming. They stack up and they're unavoidable. The Buddha would really like you to please understand this. This is part of our lives. Suffering, loss, it's just being human. It's nothing special. It's nothing personal.

So inside our individual collective pain is a story we tell ourselves and repeat and reenact over and over again. And inside that story is the iron ball in the throat. Is the item that's bringing your heart right now. It's the koan, the maybe unanswerable question of your existence right now. Right now. Right now. Again and again. Each of those kernels, whatever the loss is, whatever it is, it carries inside of it unlimited potential. That's the good news. It's not a downer, actually. As long as you're willing and courageous enough to look at it, it has infinite possibilities for you to allow it, to penetrate it. But ordinarily what we do is we look for someone else to blame.

So speaking of blame, lately I've been really into the Lojong slogans. These are these very pithy little mind trainings. They're very, very well used in Tibetan practice. Lojong means mind training in Tibetan. They're sources of Bengali master whose name was Atisha Dipankara. He didn't put them into this little pithy form of 59 sayings. That happened later. But I'm going to share with you the one that I have found really powerful. Today's slogan is brought to you by slogan number 12. Drive all blame, all blames into the one. You're probably saying, no, not that. This talk was going okay and now she's telling me to drive all blames into, by the way, this one. Not that one. This one.

It sounds like a bummer, right? But just like everything else, it's not what you think. So hang tight. The idea about this slogan is that this is your opportunity to work with your fellow human beings. This is what Pema Chodron says about this slogan. Everyone is looking for someone to blame and therefore aggression and neurosis just keep expanding. Instead, pause and look at what's happening with you. When you hold on so tightly to your view of what they did, you're hooked. Your own self-righteousness causes to get all worked up and then who's suffering. So work on cooling that reactivity rather than escalating it. This approach reduces suffering, yours and of course everyone else's.

So it strikes me that that's what we're doing here, right? What's happening in our practice in between the bird song and the bird calls and the cash shadows and the beautiful breeze and the feel of everything that's supporting us as we go. You're watching what's happening. Now I confess that gee it's really nice sometimes to blame other people, right? There's this kind of juiciness of it. You go like yeah that guy. That guy, that gal, that gal. But you know that juiciness it's just the good feeling from it. It's like expires so fast and then it really doesn't feel good.

At least in my experience when I'm blaming someone from my experience of my life, I just I kind of don't buy it. It doesn't feel right. I don't really believe it and it's not satisfying. And I think the reason it doesn't feel right is because what I've done by blaming someone else for my experiences, I've separated myself. I've made myself alone in life. I've separated this fabric that holds us all together. I've tried to. And anyway who is the one that wants to be right? Who's that? Well it's not I who wants to be right. And that's the absence of connection for me. That's suffering. It never feels wholesome to me. It never really works for me.

And what version of myself am I protecting when I want to blame someone else? Is there anyone else to blame from my experience? Well this slogan tells us exactly who is to blame. Guess who? This one. She's the only one I can blame. Even if it's not your fault, you take responsibility. In Zen, we call this eating the blame. Eat the blame. And that comes from the Zen story. And yes, it's not a koan this week. You know I always love a koan but it is a good old Zen story. So you had to wait for it. But this story is beautiful and I think you'll like it. Those of you who are in winter precepts, the precept study session might recognize this story from Aitken Roshi's book.

It goes like this. A long, long time ago in a galaxy far, far away in ancient China, a monastery abbot was eating orioke style, silent, quiet, measured meal. He's eating orioke style with the monks and the nuns, I hope. And lo and behold, picks up his spoon and inside of his spoon is a snake's head. This was a mistake. They're vegetarian. There was not supposed to be a snake soup on the menu. And a snake head in the soup in the bowl of the abbot is a serious no-no. So you can imagine how the tenzo must have felt. The abbot calls the tenzo over. The tenzo comes over. The abbot, silence, holds up the spoon with the snake's head in it. And the tenzo does this. He eats the blame. Swallows it.

So there's no point in there in which the tenzo says, oh, it was the farmer who was cutting the greens and didn't notice he'd cut up the snake. He didn't blame the soup cook who didn't notice. He didn't blame anybody. He took complete responsibility for it, understanding everything conspired in the entire universe for that snake head to be in that soup and that moment. And he ate the blame. I like to call him snake head tenzo. That was it. He didn't blame anybody. He didn't even say anything. It was over. Like that.

But what I really love about this story, other than the drama of the whole thing, is that it reminds me how none of us are in control. I mean, none of us are in control. You know this, right? It's occurred to you. No matter how mindful we are collecting the greens out in the field for the soup, making the soup, serving the soup, mistakes will happen. There will be mishaps and there will be hardship. You will have to face the fact that someone has identified something that you're involved with that looks like harm.

And you know, when you think about your responsibility, you have to remember there's a big gene pool of participants in your choices going back forever. So it's not only your suffering. It's okay. You can't blame those people, but it's not you only. You're not in charge. There will be snakes in the soup of your life. I promise you. There will also be loss and death and grief. And we can use all of these ingredients as unexpected protein in your diet.

So eating the blame is not about any kind of neurotic self-bashing. Okay. None of that or regretful fixation. Oh, I shouldn't have done that. None of that is in order here. It's not a fixation on your mistakes. We're not here to do the math. How much exactly am I to blame? You know, what's the calculus here so that I can figure out how much of the fault I should take? Take it all. I know I have done that. I know I have done that, by the way. How much of this is my fault? Let's not do this anymore. It doesn't help anybody.

This Lojong slogan is asking really how you want to be born in each moment in relationship with everyone, all these other beings in relationship with this being, including those moments when you have to deal with snake head soup. Things that are unexpected, things that you don't like, things that you don't want. This slogan is like a big bonk on your head. Wake up. You get to take responsibility for everything. That might sound daunting, but it strikes me that that's exactly what the Buddha did when he sat down. He decided he wanted to take responsibility for what this is. What is this life? What are we doing? He wanted to get to the bottom of this.

I just heard a teaching which originated with Reb Anderson, who is a great Zen teacher. And his teaching is to be a grown up, to be all the way grown up, owning your life, responsible for your life. You have to be able to say three things. I'm sorry. Thank you. And I love you.

You have to be able to say I'm sorry for the harm we've caused through our ignorance and our greed and our delusion. These are the three poisons in our teachings. We recognize that even though we're not in charge, everything that's ever happened has an influence over our decision in this moment. There's no free will. And yet we are nevertheless responsible for what we do, how we respond. Not in charge and fully responsible. That means we acknowledge that we've made mistakes. We say I'm sorry. Some people will not like your choices. Some people will be harmed, triggered, upset with you for your choices. You can feel sorry that even with the best of your intentions, you have blind spots. You're acting like everybody else, trying to do your best, trying to be a good person. But someone won't like your choices. Can you believe that anyone wouldn't like you? You're also wonderfully likeable. How could that be? But some people will have a problem with you and your choices. You have to be able to say I'm sorry.

To be a grown-up, you also have to be able to say thank you. Thank you. Even to the choices that have been hard for us to swallow. Choices that were made for us. Would you be here in this glorious life in which you are now sitting without every one of those choices and every one of the mistakes that happened before now? You would not. Can you understand that everything that you've always blamed someone else for, all those actions were never about you? No one meant you harm. They were acting out of their own suffering, just like we act out of our own suffering. Yes, it hurt. Yes, it hurts. It's harmful when people act out their suffering, not about you. And yet, you have to be able to say thank you for the opportunity to see through someone else's eyes what your actions have rippled out for them.

My friend Ocean Sensei was leading sesshin, and one of the things he said in one of his talks was that suffering is a requirement for waking up. With loving attention, kind of affection for our own wounds, we can integrate those losses and our hearts naturally open up for everyone else. What else can we say but thank you?

Finally, we also have to say, I love you. That's really not that complicated. For me, under my breath, every time I see you, I think I love you, I love you, I love you, I love you, I love you. I do, I love you, I love you. I love you, I love you, I love you, I love you. I love you. I love you. I love you. I love you. I love you. I love you. I love you. I do. I love you. I love you too, Kinko. It's not hard. If you listen to Bob on the shakuhachi, doesn't your heart just pour out love? You listen to Bill on the hawn, you pour out love. You see the way Dave moves to the zendo and your heart pours out love. My Jisha thrown into service 20 minutes before we got here. You watch her moving, your heart pours out love. I listen to your frustrations, my heart pours out love. I listen to your bells enchanting and my heart pours out love. I get goosebumps talking about it. That's not hard. I feel and see the flutter of your eyes and the wrinkles on your cheek as we steal these little shy glances at each other. It's precious this time we have together. I love you. It's easy.

But is it easy to say I love you to your health problems, your knees, your back, the iron ball in your throat, your heartbreak? This is what it is to be human. Say I love you to the intimacy of your life and everyone else's life from moment to moment. This joyous merging of a bunch of old, boring, ordinary people, not so old, some of you. Forgive me. But this is the joyous merging of life. This is what we're doing alive. We're being with each other. Everything special and heartbreakingly beautiful.

So can we say I love you to everything? Can we say I love you to everything we've each individually gone through, all the painful bits and pieces in our lives? Can we love those who are speaking ill of us, who are angry with us, who are upset with us, those who are pointing and blaming and judging us harshly? Can we love those who have fixed views about our choices? Those who are unhappy with us and suffering. Can we eat that blame?

So this kind of eating the blame requires a lot of trust, like trust with a capital T, big trust. Can we trust life? That's the question. Can we trust life? Can we trust ourselves, this ever changing, messy, imperfect, generous, confused, ignorant, deluded Buddha?

I remember hearing a phrase attributed to Michelangelo when he was 87 years old and 87 and painting St. Peter's Basilica. And he was reported to have said, encore impara, which means I am still learning. Can we be that kind and generous to ourselves, still learning to each other, to life as it is, letting go of a desire to be a better version of this, still learning?

When we can say I love you to this perfectly ordinary person, having a perfectly ordinary with its wrinkles and bumps and joys and sufferings and losses and griefs and happiness, we're saying I love you to everything. When we say I love you to this one, we are loving everyone. We love our lives. And even though this, whatever it is right here and now, is not what we expected, maybe not what we want, and it's certainly not what we planned, and it's heartbreaking some of the time. When we say yes, I accept this one, we're able to reach across time and space and Zoom and everything else to enjoy our lives and to see each other as is and to say I see you. And I see you. And I know you see me too. Just as I am. Nothing special.

One of the Buddha's main teachings is that we should learn to recognize the source of our suffering, the causes and conditions which give rise to our individual suffering. We should look at that. Look at the shadow. We should also learn to recognize our happiness, the causes and conditions that give rise to our joy. Most of us know very well the one who identifies with the suffering, the one who remembers and repeats our narratives, abandonment, loss, mistreatment, fill in the blank for your painful experiences. We think these stories are like fingerprints that they've stamped on us and we can't get away from them, but that's not true. Or maybe it's definitely not the whole picture. There's so much more.

So there's a Lucinda Williams song that has stuck with me that seems right on point. No, I'm not going to sing it to you, but I am going to read it to you. It's called Born to be Loved. And these are the lyrics.

You weren't born to be abandoned.

You weren't born to be forsaken.

You were born to be loved.

You weren't born to be mistreated.

You weren't born to be misguided.

You were born to be loved.

You weren't born to be a slave.

You weren't born to be disgraced.

You were born to be loved.

You weren't born to suffer.

And you weren't born for nothing.

You were born to be loved.

When we identify ourselves, this whole being as our wounds, as our imagined failures, as our so-called defects, we shrink ourselves. We compress ourselves. We are complicit in our own diminishment. Eleanor Roosevelt said, no one can diminish you without your consent. But our practice teaches us we have a choice. We have a choice. We can choose the wholeness of this being. We were born to be loved. We are being loved right now. The whole world is supporting us right now. Please receive it with each breath. This love starts with you.

In the Jewish Kabbalistic tradition, there's a story of a creation that's different than the traditional stories you hear. God creates these gigantic vessels, and in it he puts all the light of the world in these big vessels. Well, it's too much for the vessels, and they break. They shatter. And God is a persistent God. So he, she, they, it, however you can see, God tries again, collects the light. And he, she, they, it, this version of God, tries another approach. He takes all that light, and he decides to put it into humans. Because humans can do, but vessels cannot do. They can reflect the light back. And that's the only way the light can be contained, shining back and forth between us.

So, sitting up at Jikoji last week, in anticipation of the Buddha's birthday, sitting every day where you do, where you practice at home, sitting here, I think that's what we're doing. We're retrieving the light, recollecting our light, shining it back and forth to each other. Hopefully, everywhere we go. We birth ourselves again and again and again. Let's keep doing this. This is, I think, our life's work, day in and day out, to collect our own scattered sacred light for ourselves and for everyone.

So may this practice extend to all beings, so that everyone can choose to be a grown-up. To be free from the causes and conditions of their suffering, so that everyone can know happiness and the causes of their happiness. And may the thoughts and words and actions of our lives shine that light back. And in some way contribute to the happiness and freedom for everybody.

I'm going to close with a poem from the Therigatha. The Therigatha is a collection of poems from the Buddhist nuns. These are the very first Buddhist nuns. This is from a nun whose name was Mita, whose name means friend.

Full of trust you left home

and soon learned to walk the path,

making yourself a friend to everyone

and making everyone a friend.

When the whole world is your friend,

fear will find no place to call home.

And when you make the mind your friend,

you'll know what trust really means.

Listen, I have followed this path of friendship

to its very end

and I can say with absolute certainty

it will lead you home.

So ordinarily we have question and answer. I think I talked a long time. So you have a choice. We're going to play a game. Question and answer or a question purportedly an answer. Or I can give you a Lojong slogan. I've got them all and I really want you to try them. Just say whatever comes to you. Don't think too hard. You can't get it wrong. You can't get it right. Just say what arises. So do I have any willing victims? Really short. Really short. Tova bless you. Okay. Let me find one that I think is not too ridiculously esoteric. Some of them are ridiculous.

Don't expect applause. Don't expect applause. By the way, little background, that is the very last one of all the slogans. So in the training you would have studied them all 59 and that would be the last one. One way of looking at that is don't expect applause for having studied all these. But zoom out. Don't expect applause. What do you think?

I'm listening to that hawk out there. I'm immersed in bird song. I don't expect applause. Can you hear that?

She said she's immersed in the bird song. She doesn't expect applause. Neither does the bird. Thank you, Tova. Anybody else willing? So that's very much about recognition, right? Where that comes up in your life, pay attention. Who is it that wants recognition? I love the bird. I'm going to remember that. Thank you.

There's another one if someone wants it. Don't talk about injured limbs. Anybody?

Ouch. Yeah, this is how it is. What happens to the pain? It's when it's hot, you suffer. It's cold, you freeze. There's nothing new. Thank you. Thank you. You want one? Okay. Some of these are brutal. I can't do it to you. So. I'm going to go ahead and do a little bit of a Here's a good one. Don't bring things to a painful point. What do you think?

Well, I noticed how much I carry along. I don't know. I don't know. I don't know. I don't know. I don't know. I don't know. I don't know. I don't know. I don't know. I don't know. Well, I noticed how much I carry along. In my. Stories. Rather than saying, Oh, what's happening right now. Thank you.

Yeah. I had Doku someone on zoom early this morning. And one of his comments was basically this, like, I cannot believe how much the time. I'm like, why am I doing? How much we carry. Yeah. Anybody else. Want to slow gone. A little John slow gone. Okay. So I'm open to any comments, criticism, questions. Anything you have about. I don't know. Can go. I don't know. I don't know. I don't know. I don't know. I don't know. I don't know. I don't know.

Of sesshin practice. Because. It. It takes time for the caring along. To tire itself out. And. And for things to simplify. You know, so I can actually see what is. What is happening in a way that I can really. I can really. I can really. I can really. I can really. I can really. And not be distracted into my usual distractions. Or into my usual explanations or analysis. It's like. It tires itself out and what remains is. Surprisingly simple. I mean, also surprisingly complicated, but it's, it's not as complicated as I make it. Most of the time. I think it's a very simple. Reminder. Thank you.

Yeah, I know that one of the people that came to sesshin this time was very first time. She's been sitting with the Los Olivos sangha for a year. But it was the first sesshin. And she told us. Charming story about wanting to bolt. For the first two days. Trying to figure out how she could get out of there. Yeah, you too. I'm like, what am I doing? This is a cult. What are these people? They're all like, look at them. They won't even look me in the eye. Because we, you know, kind of stay in your meditative state most of the time. And then she had an opportunity to leave because a friend of hers had driven her up there. And this person was leaving early. And she realized, Oh, I don't want to go. I'm just getting here. It's like you say, can't go. And then you have this opportunity to. See your habits. And to not make any judgments about them in a way. To be. Liberated by just. Oh, so that's what I usually do. Or that's the way I think about that. Or that's why this. Bothers me. That's the bottom. It's like, you get past the flower. It's like, you get past the flower. Past the stem. Past the leaves below the ground and you see the root. Cause there's nothing else for you to do. You're so bored. There's nothing else but for you to look and look and look. And you get to the root and then you can go. Oh. I see you. It's a great gift. It doesn't look like fun. And the first two days are rough. And then you have this opportunity to go. Out there and look and look and look and look and then you get to the root. And that's. Potentially. Liberative. Your mileage may vary. But potentially. Liberative. Thank you. Last week. Is our emotion.

And some people, sesshin works, because it takes seven days to get out of your own way. But one of the quick ways I get out of my own way is on these chants, making them at the original. We chanted the Maka Hannya Haramita Heart Sutra in Japanese. I don't understand Japanese. I didn't understand a word of it. And I'm the head chanter. So I don't know what that leaves the rest of the people. And yet, by chanting it, I was able to get out of my own way. Because I'm like, what is this? What does that mean? What is it? I'm just trying to keep along. And then that was all Japanese. Then we did the Enmei Jukku Kannon Gyo, we did once in Japanese and twice in English. So then it's like, okay. And then I start thinking about the words. And I'm going, let's do it all in Japanese again. So it just comes back to me, get out of your own way.

Yeah, what would happen if we did that with life? We didn't ask for meaning. We didn't ask to understand every word or every line. We just said, okay, bring it on. I'll respond. Bring it on. I'll respond. I'll do my best. Bring it on. Instead of always looking for the meaning, what's it mean? What did he mean by that? What do I mean by this? Just letting it go.

The Sangha in Los Olivos asked me to start teaching the Heart Sutra, which they've been chanting in English for the last few months. And I had this incredible resistance. I'm going to teach it. But I had this incredible resistance. I don't want to tell them. I realized I don't want to tell them. Because for me, the Heart Sutra, I just chanted it and chanted like, what am I doing for months? And then I had an awareness. Oh my gosh, I think I know what they're talking about. And I want everyone to have that kind of backdoor your own door in because then it's yours. So I have to somehow figure out how to teach it without saying anything that people can cling to. Because what a great opportunity this is to use a Sutra as an example of life. You're just going to experience what's happening right now and try to meet it. No nothing more. That's it. When you're hot, you're hot. When you're cold, you're cold. Kobun used to say, when you're doing the dishes, just do the dishes. It's delightful.

Thank you, Noshi-san. Yes, Bill.

Just to comment, Meigen Roshi, actually they do the Enmei Kannon Gyo as well. And he tries, let's do it in English a few times. And he has this in his book. So they tried it and universally voted it down. And went back to the Japanese. And the reason Meigen said was actually an earlier teacher said this. That actually it's more like a mantra than something that means something.

Yeah. Because it was created in China, not in Sanskrit. And most mantras are Sanskrit. This is a Chinese mantra because the rhythm in Chinese, and I would say in Japanese as well, is addictive and you get out of your way. I always hate it when we get to the part where it translates into English again. It sounds bumpy and creepy. It probably says that in Japanese. This is a very bumpy, creepy way to chant this Japanese. I'm sorry to say it. It's a mantra like that. I think that's what we promised.

Yeah. Music is a very old, old, old. These are music. This is music. It's very, very, very old in our development. People who have degenerative brain disorders, they'll have music often. So these are chants. They must be wired the way we say them. There is a wiring that's probably firing. It's lost to us consciously, but they can come over us and teach us things that we don't know we know.

One, Fritz Stahl, a sort of Sanskrit and philosophy and Brooklyn, wrote a book. She argued that the Vedas and the learning of the Sanskrit chants in India was based on rhythms that they heard in the bird song. And so I was thinking of you. So he wrote a whole book on this and took a lot of black people. Philosophy department. We're going to talk about birds. Maybe I'll do the heart sutra next time with this rhythm. The heat. Do the heartbeat. Nobody I've never heard it that way. And he said, OK, I'm game. Next time. Next time. Any other anything? OK. Speak up a little.

I have a question and maybe you could respond to. Sure. In the beginning, you mentioned that phenomenon by which you wake up from sleep and you don't find yourself. You just like rawly experience, which lends itself to feeling confused. And then you said the self kind of builds back up and then you're back in the movie of your life. I find in my experience that that happened increasingly often when I pay very close attention in all aspects of life. And that leads me to question, is the self a stable thing that returns and is there? Is that the default state that we ought to view? Whatever that means, or is. That state prior to it the way it always is, and in fact, the feeling of a stable self is kind of being lost in thought. What do you mean?

A really beautiful question. So thank you for the question. It's your question. I can't give you an answer that's going to meet you, but I can have you think about some things about this. In fact, one of the slogans might answer your question in a way I can find it. Regard all dharmas as dreams, dharmas phenomenal experience, regard all dharmas as dreams. So both and but no shoulds. In response to you. So you exist. I see you. You see me. We're all together. And this is kind of a dream. So can you live with that? Yeah, can you live with both and because, you know, I think that's as it is. So when you experience phenomenal reality, everything coming and going and you can't hold it, that includes you. Right. Yeah. What are you going to do with that? You're going to let whatever assembles assemble and whatever disassembles, disassemble and assemble and disassemble. And this is birth and death. And it happens so fast. Birth, death, birth, death, that it's birth, death thing. It's not a separate person over there from us, from everything.

There's a lot of wisdom in this room. Would anyone else like to respond?

I'm going to say as you're talking, I think that's to me where I'm at. That's the trust in life. The both and.

Yeah. So I think it's important to have a sense of what's going on in your life. This question and for you to live this experience of this question. It's your koan right now. It'll change, but it's your koan right now. What does it mean to be you? Logan, right? What does it mean? What does it mean in this transient moving thing? What is that? Who is that?

It feels like there's just experience itself all the time. Those are the moments that I cherish the most. When I look for that staple self and don't find it repeatedly, I find that to be amazing. That I'm not on the outside of experience looking at it. I'm not on the river. I've heard it said like, I'm not on the riverbank watching it go by. There's just the river.

Yeah. Have you read Uji? Uji is a fascicle in Dogen. So can I give you some homework? Read Uji, right? This is about your experience of being time. Uji, U-J-I is a fascicle in the Shobogenzo. And read it and then come back and talk to us about it. I think you would appreciate it. Everybody can read Uji. Everybody can read Uji. Sounds like a bumper sticker. Everybody read Uji. Anybody else? It's perfectly safe here. Can't see anything wrong. Okay. Going. Going. On. Close and got that, which is, and the four vows.

I failed to stop. Give that to me once. He gives me the, he goes like this, meaning do the four vows. And I, I'm thinking he's the catcher and I'm the pitcher. He's asking me to throw.