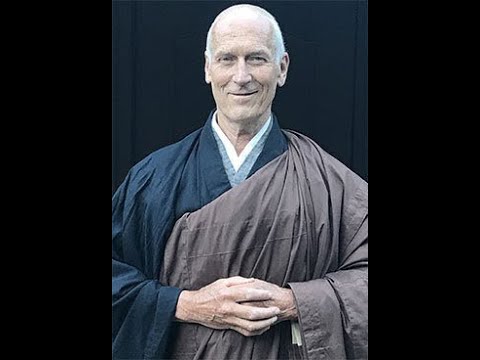

Kaizan Doug Jacobson — The Roads of Life: Pathways of Mind and Matter

Kaizan Doug Jacobson began practicing Zen in 1974 with Dainin Katagiri Roshi in Minneapolis; he had Jukai in 1977. A householder, father, contractor, and civil/tunnel engineer, following his retirement, he became a full-time resident at Jikoji Zen Center near Los Gatos. He received priest ordination in 2010 and Dharma transmission from Shoho Michael Newhall in 2015. He has led many sesshins, monthly zazenkais, periodic seasonal nature sesshins, and weekly dharma discussion groups. He also helps to maintain and develop infrastructure at Jikoji, getting his hands dirty as a form of Zen practice. In addition, he assists prisoners with Buddhist practice.

Full Transcript

Driving down mostly narrow, sometimes wide ribbons of black asphalt and gray-white concrete that separate one side of the road from the other. Narrow is a relative term. Narrow for a car, yet these roads are wide for a cricket or field mouse, a skunk or deer, to get from one side of the road to the other, including getting past the barbed wire fencing, mostly along the easements through often virgin landscapes. Us mobilized humans have almost unrestrained ability in two directions, in areas that previously had few straight paths in any direction.

These human fabricated paved roads impose structure on the landscape, beginning with carving into the land, into the hillside soils and rock, and then huge quantities made of plastic dough, of material transported in from nearby and often quite far away. The asphalt comes from oil deposits within porous rock formations worldwide. The sand of concrete, at least here in the Bay Area, comes a thousand miles away via barge from the glacial tills of Canada.

We ride in comfort with tunes or with imagining our imaginings, oblivious except for only a brief sweeping glance to touch with our eyes the unknowable extent of the terrain and the intricate, delicate, evolved living masses of this planet. Driving on these roads, I think of the countless men and women from families who became the geologists, the surveyors, the well drillers, the pipeline welders, the quarry men and women, to the haulers and those who place these products on the ground, organized in piles like ants organize the sand grains, and often newly fallen flower petals around their anthill.

Humans bring these materials to rest and they support the forceful intention of our human activity. All the dinosaur juice and plant debris, all the love making, all the food preparation, all the children held and taught and parents and grandparents tended also went into building of these roads. The compounded momentum traveling down the highway includes not only what travels down the highway, also includes the momentum that went into their making from the inception of an idea for the road to the survey on how to get it done and the will to do it.

It's worth considering this, the will to do it, for whose will is it and who got ignored or maltreated to get our will done of what some folks implemented. When we drive down the highway we take the roads we know usually, we take the roads that are convenient. In many ways moving through this life we take these convenient roads are habitual pathways, footpaths and routes of body and mind often well worn that we leave remnants of on these paths. It is helpful in our life and practice and experience and understanding when we take a different path, even the road less traveled.

And where do we actually go? On this trip everywhere I went there I was, so when I was on this trip I went there I was, so maybe we actually go nowhere. The vast wide tarmacs most of us roll down on our commutes or pathways to our destinations, some places six, eight or ten lanes wide. So we can all together be in this man-created space going off to do the worldly and unworldly deeds. And during busy times the communal density on these roads we join with others and pay homage to this me culture to fulfill our intention to get our job to our job on time and to take care of what is to be taken care of moving ahead moving forward in a what we think positive direction aiming for results, a destination aiming to connect with what we need and want.

Even a narrow road through vast apparent untouched land, virgin land, that has not been previously touched by men's tools. Our expectation as we ride atop the two-foot often two-foot thick ribbon cutting through the pristine lands is that here we get to see nature and the vast terrain as it is. And that's a bit of an illusion. Even here at Jikoji with the strong wise assistants of Jiro have made new paths around the moss garden and between the bridge and the courtyard. Sometimes even on these paths my vision becomes myopic. Focused on my balance and directional effort and traction with my feet determined to get the material to where it is temporarily going and in the process of this myopic vision I become blind to the rest of the world.

Our habits are often the pathways that get us from now to the next place of being. The surrounding terrain is asleep. As far as we can tell it's all in the past. The surrounding terrain is asleep. As far as we can tell it's often immaterial or non-existent, boring to our minds as we focus on what lays ahead or what is in front of our nose. Our practice is to stop, rest, and take a break from our standard patterns and then suddenly the terrain all around us opens up and becomes alive. Thank you Shakyamuni Buddha and all the ancestors of all genders and animal types for showing us the ways of meditation and a place to open to the vastness of this existence.

Barreling down the road leaving a little rubber and for most of us lots of waste propellant and displaced air in our wake we are so fortunate that somehow we have the opportunity to be able to take these roads to the many lands, heavens, and hell realms. Meanwhile cutting through the previously quiet undisturbed terrain, the home to the hoofed ungulates, to the rodents, the furry mammals, the serpentines, and the living relatives of the ancient dinosaurs, plus the vast arrays of other beings we call plants and trees. Each of these beings so intertwined with this existence we must pause for quite a while to fully appreciate this experience.

When we are true and in tune with the world's transience of beings and matter we respond experiencing this sweet existence with such poignancy, richness, and deep gratitude. The common Zen notion of a mountain is a mountain, a mountain is not a mountain, and again a mountain is a mountain gave new meaning to me as I stood at the opening of Titus Canyon onto its alluvial fan that spread five more miles down to the bottom of the Death Valley floor.

For many years eons a mountain is for vast eons, and the mountain is for many years a mountain. A mountain is for vast incomprehensible lengths of time the mountain wears down and becomes once again other than mountain. From boulders, cobbles, sand, and the fine matter, the sand blown around the valley to rest where other fine sand rests in large sand dunes, the finer matter often transported out of the valley higher into the atmosphere and even spread around the world as sometimes the dust storms of the Gobi Desert extend across the oceans.

These deposits of mountain wastage from the exposed surfaces of the mountain become covered, over, compressed, and eventually uplifted again and will become an exposed mountain top or hillside to disappear again and again. The apparent permanent stuff of mountains previously were from somewhere else, wastage of another mountain or hillside nearby or far away. The stuff of life was previously from somewhere else that gets covered over and back over and buried to become the base support for what follows.

The stuff of this life previously from somewhere else is with us to stockpile in our own debris piles, our own debris flows of stuff in our yards and garages along the streets and roads and often deposited in landfills of barely any kind of sorting. For a mountain, it is simple. The cracking and breaking of rock joints through freeze-thaw cycles and through the forces of plant roots finding more space and nutrients, touching molecule by molecule and they dissolve and transform into what is for them next.

For us humans, it is not so simple. This mind-body tied to countless relationships, parent-child, friend and lover, relations with bosses and colleagues, subordinates, clients and even hired guns. The debris comes in all forms of matter from flowers, food, materials for making what is needed, the pathways endless from distribution to deposition. How do we live a life where the transience is mindfully watched so the debris can flow back into the mix of all things with harmony, clarity and the benefit of all beings? The life of the transience is a life of the transience. The debris can flow back into the mix of all things with harmony, clarity and the benefit of all beings.

About six years ago, I went to a one-drop zendo sesshin, seven-day sesshin on Whidbey Island with Hirata Roshi. One of the days I went in for sanzen and with the struggles of that sesshin, I was unable to keep food down. I realized moment after moment that how similar my life was to a worm, wiggling along my path with receiving air and food and also expired air and food leaving to become food for other organisms. In that sanzen with Hirata Roshi, I said, I can see how my existence is like that of a worm. He responded, that's pretty good and he rang the bell.

When it comes to our thoughts, intentions and actions, where is this highway? Where is our road? Where is the path to take the next step? And how often do we use the worn pathways of our regular, even daily patterns to do what is needed? During this trip, I spent much time reading Pema Chodron's book, Welcoming the Unwelcome and I want to share just a little bit I know, this is probably a book familiar to many of you. She says, the reason we need to practice is in order to wake up. We have to learn to stop struggling with reality. We have to overcome our ego, that which resists what is.

Machek Labdron, a great Tibetan practitioner, said, The first of these is, reveal your hidden faults. The second of these is, reveal your hidden faults. For getting unstuck of our ego clinging, the first of these is, reveal your hidden faults. So instead of concealing our flaws and being defensive when they are exposed, she counseled us to open about them.

I'd like to close with a passage from The Way of Zen in Vietnam that is written by Gwen Giac, the venerable Joan Giac, who's a Vietnamese Zen teacher in Winchester. He relates, he uses a verse from Thu Trong, who was not a monk but was a prominent Zen master in Vietnam in the 13th century.

When the mind arises, birth and death arise.

When the mind vanishes, birth and death vanish.

Originally emptiness, birth and death in nature are void.

Illusory manifestation, this unreal body is disappearing.

When you see affliction and Bodhi fading, hell and heaven will themselves wither.

The fire oven and the boiling oil will soon cool, and the mountain of knives and the tree of swords will all shatter.

The Bodhisattvas give Dharma talks, I tell the truth.

Life is itself unreal and so is death.

The four elements are originally empty, where did they emerge from?

Don't behave like a thirsty deer chasing a mirage and searching east and then west endlessly.

The Dharma body neither comes nor goes.

The true nature is neither right nor wrong.

After arriving home, you should not ask for the way anymore.

After seeing the moon, you need not look for the finger.

The enlightened persons wrongly fear birth and death.

The enlightened fully have insight and live at ease.

Thank you.