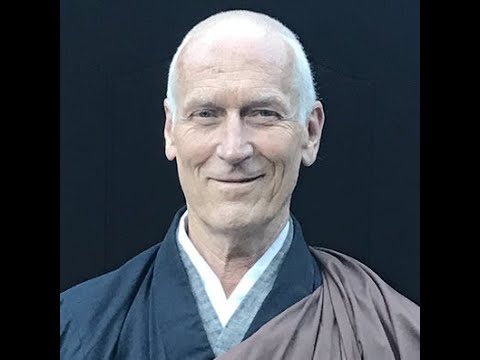

Kaizan Doug Jacobson — Embracing Impermanence and Interdependence

Kaizan Doug Jacobson began practicing Zen in Minneapolis in 1974 with Dainin Katagiri Roshi, and had Jukai in 1977. A householder, father, contractor, and civil engineer, Doug received priest ordination in 2010, and transmission in 2015, from Shoho Michael Newhall at Jikoji Zen Center. He currently serves Jikoji as one of its Guiding Teachers, and also assists prisoners with Buddhist practice. Doug also helps maintain and develop infrastructure at Jikoji, where he enjoys getting his hands dirty as a mode of Zen practice.

Full Transcript

Today I'm going to draw from a couple of important texts. One of them is from the teachings of Tongshan by William Powell. I'll start with case number 19 that goes something like this, because it relates to how we started at the very beginning.

The master Tongshan went to Qingqiao to pay respect to the old monk, Xing Ping. And Xing Ping said, "You shouldn't honor an old daughter." And the master said, "I honor one who is not an old daughter." And Xing Ping said, "Those who are not old daughters don't accept honoring." And Tongshan said, "Neither do they obstruct it."

So to neither honor nor not honor, or accept or obstruct honoring old daughters. And there's also not being an old daughter. And as a young daughter, being an old daughter, what is in that? Or is there not a daughter? Anyway, the whole idea of honoring old daughters, it's important to do. And it's important for either an old or a young daughter to also not obstruct being honored.

I know for me, when people would compliment me as a young, middle, or old daughter, I'd usually reject the compliment, which is obstructing. It's best not to obstruct, to neither obstruct nor accept honoring. I bring this up partly because one of us here mentioned that in leaving early to not be offended. And to be offended is to in a way obstruct or accept. It's best not to either be offended or not be offended in what we hear. Actually, what's best is, as John Adraka had once mentioned, to not be offended even when it is offered. I think that's really helpful, that that's neither accepting nor honoring being offended when you're not offended when it is even offered.

I think our ego, our sense of self is what fails us in these situations. It's important to accept. And it's also important to not obstruct. So to just go with what it is and let it be.

The second case I want to touch on is case number 26 from the teachings of Tung Shon. Where Tung Shon visited Head Monk Chu, who said, "How amazing, how amazing the realm of the Buddhas and the realm of the path, how unimaginable." And accordingly, Tung Shon said, "I don't inquire about the realm of the Buddha. What kind of person is he who talks thus about the realm of Buddha and the realm of the path?" When after a long time, Chu had not responded, the master said, "Why don't you answer more quickly?" And Chu said, "Such aggressiveness will not do." And the master Tung Shon said, "You haven't even answered what you were asked. So how can you say that such aggressiveness will not do?" And Chu again did not respond. He was actually quite old and maybe even ill.

But anyway, Tung Shon went on to say, "The Buddha and the path are both nothing more than names. Why don't you quote some teaching?" And Chu asked, "Well, what would a teaching say?" And Tung Shon replied, "When you've gotten the meaning, forget the words." And Chu responded, "By still depending on teachings, you sicken your mind." The next day, Chu passed away. And because of the many questions that Tung Shon had asked, he became known as the one who questions head monks to death.

So what is it still depending on teachings can sicken your mind? I want to transition here to talk about some teachings that the Buddha gave us, that if we how to hold on to them or not hold on to these teachings and yet make them part of the integral part of our lives. Because these are four essential teachings known as the four Dharma Seals. I'm getting this from Sho Haku Okamura's Realizing Genjo Koan.

And he's talking about these four Dharma Seals, which are:

First one is: Everything in life contains suffering. Pleasant, unpleasant. Pleasurable, painful. It's all kinds of suffering.

The second Dharma Seal is everything is impermanent. All things. Birth. Arise out of birth and transform into other in death.

The third Dharma Seal is everything lacks independent existence or fixed self. The codependent arising that is constantly manifesting is the third Dharma Seal.

And the fourth one is Nirvana is tranquility.

That Nirvana has been something that kind of troubled me. The notion of Nirvana, it's like, well, what is Nirvana? And it doesn't go very far in my exploration of it, but what Okamura writes about with Nirvana that to me is really helpful is this definition of Nirvana: Nirvana is the way of life that is based on awakening to the reality of impermanence and lack of independent existence. It's the way of life based on awakening to the reality of impermanence and the lack of independent existence. It is not a special stage of practice, nor is it a certain condition of mind. It is simply the way to live one's life in accordance with reality.

When we truly see impermanence and lack of independent existence, we understand deeply that we cannot hold on to anything and that nothing lasts forever. Seeing reality encourages us to stop clinging to our lives and their contents and give us the chance to open the hand of thought before life forces us to open it. This seeing and accepting and letting go is Buddha practice.

So there is samsara, the suffering, and there is Nirvana, this tranquility, this ultimate tranquility, which occur simultaneously and in the midst of samsara, while we are paying attention to our existence and we're aware of the impermanence of what is underway, whether we're sitting and watching our breath and the impermanence of each breath and this body. As well as the lack of independent existence. That how the air helps makes our body and the earth supports our whole body when we simultaneously are aware of impermanence of all things and this codependent arising of what's going on with the conditions before us. That gives us Nirvana, that gives us a fundamental tranquility that we can rest in.

To see impermanence and lack of independent existence, moment after moment, we can see that clinging is unnecessary. We can meet obstacles and difficult situations in seeing their impermanence and lack of independent existence. We can see the conditions arising into this existence, and we can navigate through these conditions with a dynamic beingness of tranquility and a sense of just this is it. With our whole body and mind being with the clear knowing of impermanence of this breath, of this body, of this moment's thoughts and concerns, this moment's sensations. And then also seeing the linkage and the beginningless connections of what is before us. This brings us a serenity of tranquility to meet our life moment after moment.

And I think it's Nirvana, the practice of this practice that we have this. Nirvana is not necessarily a quiet state, it is actually a dynamic tranquility of awakening to the impermanence and lack of independent self in all things simultaneously moment after moment.

Kobun Chino Otogawa Roshi once said that if even one part of you is OK then you are entirely OK. As things are basically going along OK, they should be allowed to continue. So in our moment after moment to realize some part of us or the situation we're in is OK, we can also rest that basically we are entirely OK. It's when we start pointing out "oops this is not OK" that we're suddenly entangled.

So how to move about with this sense of OK, of with our impermanence, with our lack of independent existence, of seeing this bounty that we're in the midst of. In the morning when we anticipate our first cup of tea or sip first cup of coffee, we're even anticipating the smell and the taste and the touch, the warm touch of the cup. And even anticipating the warm sensation of our throat and the sensation that we feel after consuming the tea or coffee. And that desire in the anticipation, there is desire in that anticipation. That involves our six consciousnesses. And it also involves the five skandas. The five aspects of being form, feeling, sensation, thought formation, and consciousness.

And after drinking the tea, after drinking the coffee, we suddenly turn our attention away from that anticipation and that experience. And we're on to the next one. And this is the endless cycle of suffering that we are in the midst of. Jumping from one desire, transitioning through it and moving to the next one that in a way marks our day and what we need to get done.

And in the midst of this pleasure and this suffering, in the moment when it happens, how momentary is it? Kobun once told a student that the experience of pain, say the pain in the knees, that when we experience that pain, the pain is already that sensation is already passed. That pain that we feel in that moment, we say, "Oh, I'm feeling pain" and we're looking at a pain that has already passed and we're in the midst of maybe new pain. Or the continuing of that sensation, but our reaction to it is of something that happened a moment ago. And this agitation forms around that. Worrying about this experience that just a split second ago has passed and yet we're experiencing this pain.

And in the midst of whatever pain we're in to see it as it is, to accept it as it is, to honor it and not obstruct it as it is, is embracing all of it and seeing its impermanence and seeing its interdependence with all things. With everything, understanding everything is impermanent. The second Dharma seal: birth becomes death, pure becomes impure. Maybe impure also becomes pure as we're working on something. Large becomes small and small comes back together to form large. And there is no thought, there is no sensation, no object that has permanence.

The third Dharma seal that everything lacks independent existence. We understand that when we also look at the 12 links of interdependent co-arising. And finally, the fourth Dharma seal that Nirvana is tranquility. There is samsara and there is Nirvana. Is it that they are independent? Is one a state to avoid and one is state to achieve? Words and their meaning sometimes are illuminating. However, the word Nirvana has not really pointed to anything useful to me all these years. Kind of a nebulous word, but this. Of course, Nirvana is also the name of a famous rock band. Anyway.

With our whole body to simultaneously be aware of the impermanence of what we are in the process of and the linked conditioning to this existence with all things simultaneously brings us serenity and tranquility. So I hope that the practice, this essential practice of awakening to impermanence and codependent arising simultaneously is helpful to meet our day, our life moment after moment.

I'm going to close with a poem from Farid Attar, who lived about the time of Dogen, a little bit before Dogen, in the Middle East. And it's from his "The Conference of the Birds." And a bird asked the question to the Hoopoe about audacity.

The bird said, "Is audacity allowed before such majesty? One needs that audacity to conquer fear. But is it right in his exalted sphere?"

And the Hoopoe answers him, saying:

"Those who are worthy reach a subtle understanding more.

None can reach and none can teach.

They guard the secrets of our glorious king

and therefore are not kept from anything.

But how could one who knows such secrets be

convicted of the least audacity?

Since he is filled with reverence to the brim,

a breath of boldness is permitted him.

The ignorant, it's true, can never share

the secrets of our king. If one should dare

To ape the ways of the initiate,

what does he do but blindly imitate?

He's like some soldier who kicks up a din

and spoils the ranks with his indiscipline.

But think of some new pilgrim, some young boy

or girl whose boldness comes from mere excess joy.

He has no certain knowledge of the way

and what seems rudeness is but lovely, loving play.

He's like a madman, love's audacity,

will have him walking on the restless sea.

Such ways are laudable. We should admire

this love that turns him to a blazing fire.

One can't expect discretion from a flame.

And madmen are beyond reproach or blame.

When madness chooses you to be its prey,

we'll hear what crazy things you have to say."

Thank you.