Ōshin Jennings — Polishing the Rooftop: Zazen as Expression of Awakening

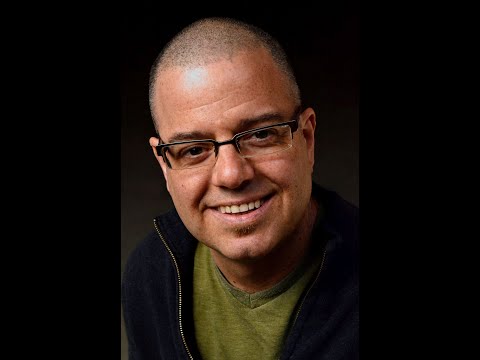

Ōshin Jennings is the founder and guiding teacher of No Barriers Zen, a Zen Buddhist community in Washington, DC. Ōshin is the first known Deaf Buddhist priest, and he has made it his mission to use his experiences as a Deaf and disabled practitioner to help make meditation practice and the Buddhist teachings accessible to all people, especially those with historically limited access.

Ōshin has been a student of Buddhism and Zen for over 25 years. He ordained in 2009 and is currently a student of Michael Kuzan Shoho Newhall Roshi, the abbot emeritus of Jikoji Zen Center in Los Gatos, California who is a Dharma heir of the late Kobun Chino Otogawa Roshi. Shoho Roshi gave Ōshin Dharma transmission in 2022. Ōshin has also studied Buddhism throughout the US, and abroad in Japan and Southeast Asia. As an artist and psychotherapist Ōshin is particularly interested in the intersections of meditation, mental health, and creativity, which serve as key themes for his teachings as well as his research. When not on the cushion you will find Ōshin out in nature or working in his art studio.

Full Transcript

So, thank you again. Thank you to Nenzen Sensei, my friend, my dorm assistant, my mentor. It's so good to be here. And you guys have been playing host a little bit and it's really warm and really special. I'm really happy to be here.

I'm going to kind of do something a little different. We talked about it at dinner briefly. I have an idea that some of you may have some questions. I have some questions. And if you like, maybe you have a question already and you'd like to tell me, or there's something you're practicing with right now. And you'd like to tell me about that. And I can maybe try and keep that in mind and maybe kind of weave it in to what I'm talking about. Do you have anything that they're practicing with that they're considering? Any questions?

"I'm practicing with... If all... If true nature is here, in the present, and I admit it is all, I'm going to relax into that and stay taut enough to not get lost in the car."

Thank you. Anybody else have a question? Please also tell me your name.

"What's your question? I'm reading a book by Pema Chodron called How We Live Is How We Die. And she talks about the importance of frame of mind and how important it is when we die to have a peaceful frame of mind. And I was wondering what your thoughts are about that or you can read that in."

Yeah. Thank you. Anyone else? Anybody else help?

"So, looking at death in very practical ways, the actual arrangements of death and dying, burial, or cremation, those kinds of questions necessary now with my husband and so on making plans. So, we have the new grand baby and so we have birth death, which is hinchy, that is the combo, birth death, I remember the term. So, just similar to what you mentioned of how do we live with death close?"

Yeah, I have a little talk prepared for tonight and maybe some of these questions can come up and maybe we can talk about a little bit after at the end to save some extra time for Q&A. This is actually a talk that you've heard. This is a talk that we thought would be good to get here as well and also give us an opportunity to record it.

So I'd like to tell you a story. In China in the beginning of the Golden Age of Zen, so we're talking about some time in the 700s, there was a monk named Baso Goitsu and he was practicing at Baiyuan Temple, which is still there. You can visit it. And Baso was practicing there when he met his teacher, Nangaku Ejo. Nangaku Ejo was already a pretty accomplished monk, whatever that means. But he had a certain eye, and he could see that Baso would make a good student who's watching this young monk practicing quite earnestly.

And one day outside of the Zen Dome, I pictured maybe sitting in a courtyard like this. Master Ejo walks by and he sees Baso sitting really strong. And he says, "Venerable monk, what are you trying to accomplish by sitting Zazen?" What a question. What are you trying to accomplish by sitting Zazen? And Baso said, "I aim to become a Buddha."

So Master Ejo picked up a roofing tile from the ground in the courtyard, and he started to polish it. This is while Baso looks up. You can picture him almost like sitting, this young man sitting really strong Zazen. This little clay is being kind of enacted for him. And finally Baso says, "Why are you polishing a roof tile?" And Master Ejo said, "I'm polishing it to make it a mirror." To make it a mirror. And Baso said, "You can't turn a roof tile into a mirror by polishing it." And Master Ejo said, "Just as polishing a roofing tile won't ever make it a mirror, sitting Zazen won't make you a Buddha."

Wow, okay, there's that. But what's really interesting is when I was looking at this story, most people kind of stop there. That's the end of it. But there's a few more lines to this case. And it goes on and it says, Master Ejo says, "Just as polishing a roofing tile won't ever make it a mirror, sitting Zazen won't make you a Buddha." And I asked, "How should I proceed then?" Master Ejo said, "If you hitch an ox to a cart and the cart doesn't move, do you whip the cart or the ox?" And he said, at this, Baso was struck wordless.

So Baso clearly understands that polishing a roofing tile will never make it a mirror. But he still is operating under this kind of idea that this false belief that he can kind of grind himself into a Buddha. He's going to work it all out on a cushion like that. And while we can admire his energy, this focus, like, we need strong practice, you know. It's obvious that he's missing the mark. And I can't help but think of my own practice. How many times I just really kind of beat myself up on the cushion and in my life. So I think it's an energy we can relate with. It's something that we can understand. And it's part of all of our practice in some way, some shape, some form.

And so Master Ejo sees this monk, sees his determination and sees perhaps even his potential. And he felt maybe, hey, maybe, hey, this would be a shame to let all that energy and potential kind of go to waste, get all screwed up on the cushion like that. This is what we call arousing the aspiration of enlightenment. This is what Dogen called arousing the aspiration of enlightenment. And so Ejo in his compaction, he sets up this little forest in the courtyard. And he's like, hey, you're lost in the weeds. Oh, look. Some discarded broken thing. Oh, you know, it's like very natural. I'm just going to sit here. I'm going to rub it with my sleeve for a while. And I'm going to see if this monk can pick up the trail again. Just leaving little breadcrumbs.

And perhaps sensing the strong resolve, the strong practice in this younger monk. Master Ejo Uitsu. Also is usually called by his original Chinese name, he's a Chinese monk. He's known as Master Ma, great master Ma, or Ma-zu. But this was before he was Master Ma. And what's really interesting is because Master Ejo was his preceptor. He's the one that was his main teacher. And it seems that maybe this call, this little teaching story is about their first time meeting. It was really nice. I'd love to have our words written on the first time we meet.

And so his name, Ma-zu Uitsu, translates roughly to his Dharma name, translates roughly to ancestor horse one path. I picture this strong energy, this horse, this strong steed, that clarity in that direction. And Ejo comes along and lets him know, you're a little off. So how is his aim life? His aim is off because no amount of sitting is going to make you a good man. No amount of polishing will turn Terracotta into a mirror. And thinking that it's the tiles fall isn't going to change anything about that situation. But if that's what you need to do, then go ahead, polish. Polish to your heart's content. It's okay.

But if you come, if Santa Barbara's in, say, oh, you joined us at Jikoji, and you say, I'm going to sit 1000 sesshin and I'm not going to miss a period of Zazen in the next 10 years. Okay. And you still don't become a Buddha? Blaming yourself isn't going to change anything about that situation either. Maybe we all somehow start with this idea that Zazen practice leads to Buddhahood, or leads to enlightenment, or leads to the cessation of suffering or whatever you want to call it. Maybe it's the end of our suffering is just a few more of these butt-busting, knee-breaking sessions away. Maybe it's just a little wisely, you know. A few more of these sleep deprived circuses we put ourselves through. But Zazen doesn't lead to awakening. Zazen is the expression of our awakening.

So as the story continues, Master Ejo adds another little blow. Master Ejo asks, "What do you whip? The cart or the ox?" If you, new guy, if you hit your ox to a cart and it doesn't go, you whip the cart? You whip the cart? Nothing happens, right? If you hitch your ox to a rooftop. If you hitch your ox to Master Ejo. If you hitch your ox to that huge beautiful tree outside the Santa Barbara Amtrak station. If you hitch your ox to Buddhahood. What happens?

So Master Ejo holds nothing back in his generosity. He says, hey, maybe whipping the cart is the same as yours, Zazen. He's saying, it's your mind. It's the ox, it's not the cart. Besides, you can't use Zazen like that. You can't use Zazen. You can't use Zazen. Zazen can use Zazen. So get out of the way. Let Zazen sit Zazen.

So Pema Chodron said, already maybe we can answer some of these questions. I think we're reading the same books anyway. Pema Chodron said, meditation practice isn't about trying to throw ourselves away and become something better. It's about befriending who we already are. Or as the jazz musician, the colonial monk said, a genius is the one who is most like himself or herself.

So if you're sitting there and you're thinking, OK, well then whip the ox. Right. That's what you're saying. Right. Whip the ox. Well, what you're expressing with whip the ox is actually just our habit of separating the whole source of our suffering. It just further perpetuates the dualism and is not the point of the story. For the point of the story, we have to look with a different eye. We have to look the way that Master Ejo looked at young Master Ma, at little Baso.

So by leaning in to that perceived separateness like that, it's not taking you any nearer to that which you seek. And by the way, don't seek. Trust it. Trust it instead. Trust it because as the ox moves, so does the cart. It's practice in life. It's practice in that. It's ox and cart. Just like how the ox and cart moves, so does our body, mind. Just like how the ox is well suited for this work and the cart was made for this. So too is your body made to sit down there. And so too is our mind made for awakening. And your zazen is one of the functions of your awakening. It's not a product. It's your enlightenment already, if you will. Buddha's already here. It's already here. You're not going to attain that awakening. To attain the Buddha. You're just in the core of the enlightenment. You've already got it.

It's like Jack Kerouac said, equally empty, equally to be loved, equally a coming Buddha. Have you ever heard that quote before? Some of the orders and practices are hip to the Dharma Bhaam stuff. And I like the beats. I wanted to track down the source of that quote. It's from a longer passage. And it says, "I sit down and I say, and I run all my friends, my relatives, my enemies, one by one in this without entertaining any angers or gratitudes or anything. And I say, like Jaffee Ryder, equally empty, equally to be loved, equally a coming Buddha. Then I run on and I say, David O. Selznick, equally empty, equally a coming Buddha. Though I don't use names like David O. Selznick. Just people I know. Because when I say the words, equally a coming Buddha, I want to think of their eyes. Like you take Morley, his blue eyes behind those glasses. When you think equally a coming Buddha, you think of those eyes and you really do suddenly see the true secret serenity and the truth of his coming Buddhahood. Then you think of your enemies eyes."

So if you're focusing on becoming a Buddha, what happens? You miss the Buddha where you are. You miss the Buddhas all around you. I was getting on the train, the Amtrak train to come down from San Jose, from Jikoji, to come down here. And I very nearly missed my train. You're in a strange city, a strange town. Don't know where you are, don't know what you're doing. Trying to make sense of the one working board. What does that say? Which way is track 11? There's only four tracks. How does that make sense? You know, it's just like all of this stuff. And I'm lost. I'm in the weeds. Finally running around and I see this male. Taller than Karlin. So I hide this in. And everybody's bringing in tickets. I said, oh, no, you go over there. You line up here. You do this. You do this. I said, that's the guy. It was my Buddha.

So I hold out my ticket. Please, sir. And he lines me up and tells me what to do. And when the train comes, you go in here. And I realized I'm talking to an autistic man on the spectrum. And he doesn't work here. He's a rail fan. He's a train fan. And so he's just helping. And so he's helping. And he's giving me all the information I need. And then you're going to go left. And you're going to do this. And then you go on. And then you go up the stairs. And you sit up on top. You want to sit on the left side of the train so you can see the water. You want to sit on the other side. And then he goes, excuse me. You can't smoke here. And he runs off to go and get something else. OK. And it's just like, it's all here. It's all here. Equality. Equally to be loved. Equally a common Buddha.

And that's it. We have to see the Buddha and those around us. We have to see the Buddha in ourselves. Or at least to see the equally empty part, the equally to be loved part. And as soon as you create this posture, there it is. As soon as you create it, the Buddha has been revealed. Yeah. Lara Buddha. Karlin Buddha. The Tova Buddha. Nelson Buddha. Michael Buddha. New guy Buddha.

Another Pema Chodron quote. Holding onto beliefs limits our experience of life. That doesn't mean that beliefs or opinions or ideas are a problem. It's the stubborn attitude of having to have things be a particular way, grasping onto our beliefs and opinions that causes the problems. Using your belief system in this way creates a situation in which you choose to be blind instead of being able to see, to be deaf instead of being able to hear, to be dead rather than alive, asleep rather than awake.

As people who want to live a good, for unrestricted, adventurous, real kind of life, there is a concrete instruction that we can follow. See what is. See what is. Without calling your belief right or wrong, acknowledge it, see it clearly without judgment and let it go. Come back to the present moment. From now until the moment of your death, you could do this. You could just see what's happening and be fully intimate and present with that, without movement, without person, with nothing else, with nothing else. And then watch all the details. So just kind of take care of themselves. Here's my ticket. I don't know where to go. What to do? I'm going to miss my train. Just go here? Oh, I know. Don't smoke. Go over. I know. It's all here.

So our path isn't about becoming something else. It's rather about unbecoming what truly isn't us. What isn't truly ourselves so that we can truly be free. When we've released that. When we've released all that criteria. So you don't whip yourself. You don't whip yourself. I'm not enough. I'm not that. I'm not the right kind of Buddha. This kind of Buddha isn't needed. Each Buddha is needed. All the Buddhas are needed. And each needs to hold its own Dharma position.

And what if instead of whipping the ox, we tried to guide it? I know my ox sometimes lets me ride in the cart. Sometimes lets me ride on his back. Sometimes I get down and I walk this ox around. Sometimes I have to pull it by the ring through his nose. What a friend have on this path, this ox. Yeah?

So I wanted to tell another story because we just kind of came out of the Panjulay session. The session that one of these four traditional sessions that COVID helped establish at Jikoji. And Panjulay means birthday. This is a Buddhist birthday session. A big birthday party. And we accommodated with this Buddhist birthday celebration a couple of weeks ago. And we offered flowers and we ladled sweet tea over the Buddha statue. And it was a very tender, lovely little ceremony. And every year around this kind of Panjulay time, I

It's actually the name of one of the Jataka tale books, one of the modern translations. Once the Buddha was a monkey. So I'll read you this story. And it says, Once upon a time in Gandhara, in an old kingdom, and what is today in northern India and Pakistan, there was a place called Takasila. That place, the enlightenment being was born as a cow. He was an excellent and strong cow and he was bought by a wealthy landowner who became very fond of this gentle and noble ox and he named him Delightful. It was a very special, it was a very good name. Named him Delightful and he took excellent care of him. He gave him only the best feed, gave him a lovely place to live.

And when Delightful grew into a big strong ox, he thought, this generous man has given me everything an animal could want. Good care, plenty of food, water, and because of this, I'm incredibly strong and I can pull the heaviest loads. I would like to repay my master by using my strength to benefit them. And so one day Delightful said to his master, find a wealthy merchant, I love this, it's got a talking ox, it's great, so Delightful said to his master, find a wealthy merchant in town who has the strongest oxen and challenge him, saying your ox can pull a hundred carts.

So the master found a merchant down in town where the merchant was boasting to have strong oxen, some of the strongest oxen in the land. So he said, you, I'll challenge you. I have an ox that can pull 100 carts. There's no ox stronger. And the merchant said, there's no ox that strong. I will bet you 1000 gold that he cannot. So they set a challenge with the merchant setting up 100 carts and he decided to load them with rocks to make them especially heavy and challenging. The master in preparing the ox for the challenge bathed him and fed him the finest grains. He's strong a beautiful garland of flowers around Delightful's neck. The master then led Delightful down to town where the 100 carts were waiting.

Seeing the merchant and the assembled crowd, the master couldn't resist making himself seem important. So he yoked the ox and started to whip at Delightful. Pull you dumb beast, pull. I, your master, command you. He said, while whipping the air above the ox, Delightful thought, this challenge was my idea and I have never even disobeyed my master. Yet how he beats me and insults me. So Delightful stayed in place. He wouldn't budge and the master lost the challenge and the 1000 gold coins. But more than that, it was the blow to his pride. He went home sulking.

Back home, Delightful grazed peacefully and the master distraught said, Delightful, how could you do this to me? And now you're grazing so peacefully after I was so badly embarrassed in town. Delightful said, you call me a dumb animal and insult me in front of everyone. In my whole life, have I ever stepped on you or broken anything? You know, made a mess where I shouldn't. I behaved like a dumb animal. No, Delightful. No, you haven't, my beloved pet. Said then why crack the whip above my head? Why call me dumb? The master acquiesced and so Delightful said, find the merchant, challenge him again. And this time 2000 gold coins.

And again, they found the merchant and of course he accepted thinking, easy money. And so the master bathed and fed Delightful and brought him to town in front of the assembled 100 carts. And this time the master gave up the whip, picked up a lotus blossom and touched it to the forehead of Delightful. He looked fondly to the ox and said, as if he were his own child and said, Delightful, my son, will you do me the honor of pulling 100 carts? Much to everyone's surprise, Delightful pulled the heavy carts and to the last one stood in the place of the first. The merchant was shocked and paid the 2000 gold coins. And the assembled onlookers further showered the master and Delightful with gifts. And more than his winnings, the master gained humility and respect.

What a charming and Delightful story. And while this Jataka tale traditionally is used as a kind of like morality play, Aesop's fables kind of thing, its theme is usually like, respect brings honor. And it's a very cultural thing, but perhaps you'll also see what I saw in this story, which is that there's something there for us in the way that we work with our own minds. If we wanna keep following this metaphor of ox and cart that way. And I think that's what we're here to do. I think that we're here to kind of work on ourselves in that way and kind of put down the whip and remember, remember. All I have to do is remember.

Just before the sesshin, a couple of the residents and teachers were sitting around on the table and they were talking at the breakfast table something about all of our kind of favorite ways to talk about enlightenment. And none of us liked talking about it. And none of us liked using the word. And so instead of attain Buddhahood, somebody was reminding us how Kobun would say, return to Buddha. Just say, return to Buddha. Instead of attaining the great lay. Return, return, return. And Pamela said, recollect, to recollect, to recollect our Buddhahood. Gather ourselves back up. Just gather yourself back up. And there moves the cart and there moves the ox. And when those thoughts arise and we find ourselves getting stuck in our story, it's just like, oh, it's okay. That was just a moment where I forgot who I truly was. I can now recollect. I can now recollect and come back and return. Return to Buddha.

I'm really looking forward to practicing with it and returning to Buddha and recollecting our Buddhahood. And so on in my life. It's the last thing I'll say. Just sit. Just sit. Just show up as you are. Not the one you think you are. The real you. The equally empty, equally beloved, equally a common Buddha you. Thank you for your attention. So I have a little time for some more questions.

Sensei? Yeah. Can you stand out of here? I'm thinking about the light of hope. I think it's just thinking about the light of hope. Do you still like that? Yeah. Do you still like that? I still like that. Yeah. Put it down. Put it down. Put it down on the will. It's the acquiescent mind that realizes itself. As we say. It's surely something I could buy. Or I could buy something I could buy. I could buy something I could buy. I could buy something I could buy. Or I could change. I could buy. That would do it. No, right around that. I tried all those things. That's all that sensei means in Japanese. It means one who's gone before. I've made those mistakes. Listen to me. Thank you.

So yeah, so we have any questions or comments? Yeah. I'm just trying to think of what acquiescent means. I need a definition. Is it acquiescent mind? No. Just putting down the word. So it's the accepting mind. I think there's a quality of acceptance that's in it for sure. But I think there's a quality of kind of releasing. The problem is that, I've done this before, so you don't have to do this anymore, right? Is that we think letting go looks like this. But letting go actually looks like this. There's still doubt. There's still pain. There's still confusion. Sometimes it goes. And sometimes it comes. Not doing this anymore. We were talking about this. Talking about this. All the negativity that we use. And when you release it, you don't need to use it anymore. All of this energy gets freed up for. One of the great things. And when you're not, whipping, whipping. It's a little bit easier. It's a little bit easier. And the oxygen's so grumpy.

So to acquiesce, to release, to release, to release, is in all of this. I think it actually comes more from like, the Taoist side, almost about practice. So maybe it was a Chan, like a Chinese side of story. This teacher had a student who was working really hard, kind of maybe like Basso, kind of like a great master Ma, and said, I have a teaching for it. I want you to go down to the river, and I want you to pick up mud. And I want you to rub it and polish it and make a mud ball. Perfect ball, perfect sphere. And then you place it on the banks of the river. I want you to do that so you get 100 perfect mud balls. It's a lot of work. Polishing, polishing. Huh? So that's more up. And then he goes to his teacher and says, I've done it. Teacher's good. Now one by one, we each will run them into the river to dissolve. That's not this. That's not this. That's hanging on. That's gripping for dear life. But if it could be this, okay.

But Oshin, he's taking advantage of him. What about all my preciousness and all of this? Show me. Show me the one he's taking advantage of. Show me the one. Where is it? I can't find him anywhere. Yeah. There's something very nice about dissolve. I think I'd be happier to dissolve when I'm going to make mud balls. But that's where I have to acquiesce, right? There's another great, I think from that same collection, there's a more modern story where the teacher said to a student, the teacher said to a student, we wanted to know about these qualities of mind. Why do I practice this? The teacher said, mind like sieve. That's really unappetizing. What does that mean? What does that mean? And the student tried to practice this. How to hold on to these things, how to work with things when they... Say, I can't. The teacher says, give me that sieve. And chucks it into the river and goes, mind like sieve. Dissolve, dissolve. Same story.

I might have time for one more. Doesn't even have to be a good one. Oh, there's somebody, there's something in the chat. So somebody broke into my house and stole all the lamps. I am delighted. Any other questions or comments? That was all perfectly clear now, I mean. Good, because it wasn't for me either. So we're in the same sieve. I think sometimes we have to learn to look with a different eye. I think maybe it's around here somewhere. And there's Dido, oh, she. And there's Dido, oh, she. Is that not what I'm asked to say? Sometimes dharmas are dark to the mind, but radiant to the heart. I think that's really true, because sometimes... Okay, what does this unoxenium delightful have anything to do with too late mortgage payments? Cancer diagnosis. Watching your spouse fade. I didn't have another surgery when I got home. Remember the first, gotta find balance to let go sometimes. If you can do that. It's... Oh, okay. Okay.

I really appreciate looking with another eye in this discussion. I've heard of it, but somehow I hear it from you. It's new, looking with another eye. And I suggest to me that when we have a response to something at all, offense, sadness, anger, anything that arises, this looking with another eye, we can make this choice in that moment, to look with this other eye and return to... That this other eye requires us to take the set of glasses that we're wearing and kind of put them off and just kind of keep peeling off the glasses, in my case, it's the glasses, or keep peeling back. Whatever it is that we think we're seeing or feeling until there's nothing left, but what's actually here. And so I really appreciate this other eye. I'm gonna use it in my own experience and practice because it reminds me, again, because we practice, we get to make this choice using another eye in any given moment. Whenever anything arises, we have the right from the color to use another eye. So I really appreciate this. Thank you.

Yeah, and the great master Tozan said, seeing with eyes, nothing is seen, hearing with ears, nothing is heard. But seeing with ears, nothing is hidden. Sounds like a dark to the mind stuff maybe, but I think it's radiant to our heart. I think it's really radiant. But to really listen, to really see what's actually going on. Not my story about what's going on, but actually see. The only way I can see is I have to let go of the thing that's keeping me from seeing. I feel like the only way that I see up and over my ego is to sit down way low. Mm-hmm. Man keeps increasing and And the whole family is not boundless and I love you. The sun surpassed the whole kind of world. Well, this is the question that I started in the beginning of the year.