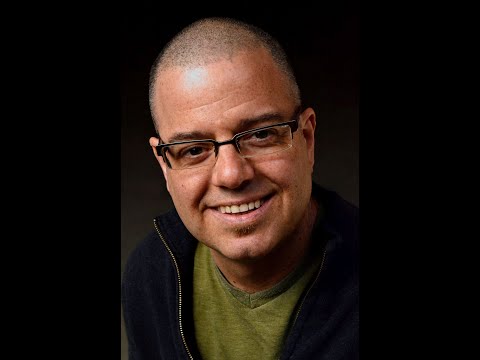

Hozan Alan Senauke — The Bodhisattva's Embrace: Dogen's Four Embracing Dharmas

Hozan Alan Senauke is abbot of Berkeley Zen Center, in the Soto Zen lineage of Shunryu Suzuki Roshi. He is an activist, writer, father, and musician, an honored "pioneer" of socially engaged Buddhism.

In 2008, Hozan founded Clear View Project, offering Buddhist-based resources for social change in the U.S. and Asia—supporting movements for human rights and empowerment in communities of need in India, Myanmar, and around the world.

Hozan’s most recent book is Turning Words: Transformative Encounters with Buddhist Teachers (Shambhala, 2023). He writes “The Bodhisattva’s Embrace” column for BuddhistDoor Global, and is the author of numerous books and articles on Zen and engaged Buddhism.

Full Transcript

We're having a work day here at Berkeley Zen Center, which I'm going to join after this talk and after lunch. It's kind of a rainy overcast day here. Surprising. The weather just changes every day. I have not been to Santa Barbara in quite a while. Have I met any of you down there? No, because I used to come down. This is quite a while ago. Every year, when the Zendo was in Tony Johansson's house up in the hills, we had a weekend and we'd do a one day sitting and have a couple of talks and it was quite lovely. That was a really wonderful connection. But things change. Pandemics arrive. And so now we're meeting on Zoom. So I'm happy to be with you here.

I've been thinking, as I'm sure many of you have been thinking, feeling, grieving about what is unfolding in the Middle East, in Israel and Gaza. I have a lot of thoughts and I've written about it a little bit. And I have no solutions. But it points us back to how we want to practice in the world. I think at the very least we can raise questions about how we are conducting ourselves in relation to those with whom we disagree, those with whom we may be in conflict. What does our practice say about this?

So I want to return to a teaching of Zen Master Dogen's that has been very important to me over the last more than 20 years. And that is a teaching called Bodhisattva Shishobo. Which is translated sometimes as the Bodhisattva's four embracing dharmas. Or if you have a copy of Kazuaki Tanahashi's translation, it's "The Bodhisattva's Four Methods of Guidance."

Several years after returning from China in 1227, Master Dogen built the first Japanese Soto Zen monastery, Koshōji in the southern reaches of Kyoto. And there he created a really vibrant setting in which he could practice, teach, write, and develop a monastic community that was centered, that was devoted to his zazen centered approach to Zen and to Buddhism. This was all in the social climate of what's called Kamakura Japan, in which there was a real flowering of new and popular forms of Buddhism that were available to ordinary people, not just to the elites which previous monastic Buddhism had been.

So we had arising roughly the same period in the 13th century, you had Dogen and his approach to Zen, you had Shin Buddhism, you had Shinshu and Jodo Shū, which is a Pure Land school, you had Nichiren Buddhism which focused on the Lotus Sutra as a primary text. And all of these offered very straightforward practices for people who really wanted to be awake in their lives. At the same time, the society that was taking place around them was really marked by feudalism, political tensions and civil strife, which sadly played out among the Buddhist sects. You had warrior monks, you had one monastery attacking another monastery and burning them down. All kinds of things like that.

So in May of 1243, really in the midst of this kind of internecine violence among Buddhists, Dogan Zenji wrote this fascicle, Bodhisattva Shishobo, which is the 28th fascicle of his masterwork Shobogenzo. I'm assuming that you guys are part of the cult of Dogan, right? This is not a name that is alien to you. You probably read quite a bit.

So he wrote this in May of 1243 and presented it to his community. I believe as I read it, it's a very accessible piece of writing. It's very practical. And I think that he offered it to his community for guidance as to how to respond to their difficult circumstances. It's quite possible that they were under threat or actual attack. And at the top of their minds was the fact that he wrote this in May, in late July. They packed up and they left Kushoji behind completely. Can you imagine what that was like? To leave this place. They've been there for 13 years. It was a beautiful temple complex. It was what they knew as home. And they packed up and they left to the very remote area of Echizen province, which is where within the next few years, he created Eheji, which was named the Temple of Eternal Peace.

So he, Dogen, wanted to lead his community out of the cauldron of conflict that existed in Kyoto. And I can only imagine or I can't imagine what a wrenching departure that was. And I think of it today as war and violence burn through Israel and Gaza. And as we see the playing out and extending of decades of intergenerational trauma. There must be some alternative to cycles of hatred and violence.

So what did he present? Shishobo presents four methods, four approaches to how we interact on a social basis. Four ways to embrace each other. So these four embracing dharmas are: giving or dana, kind speech, beneficial action, and what Dogen called variously translated identity action, which is kind of awkward term, or cooperation. And that's how some recent scholars translate the Japanese word. So giving, kind speech, beneficial action, and cooperation. And you can see each of those is a way in which we are in relationship and communication with others.

This particular teaching was not something that he invented. It was already ancient practice. And you can find it in the Sangha. It's called the Ali Sangaha. And it's variously translated as four ways of showing favor, or the foundations of social unity, or the bonds of fellowship. And you can find this in the Sangha Sutta. And also you find it in quite a number of the major Mahayana texts. As you read them, it just appears.

For me, I had this opportunity to work with some years ago on a translation of this. And actually that whole translation in a longer essay is available in my book "The Bodhisattva's Embrace," which you can find online. But this embrace, so embrace means to encircle. I put my arms around you and you put your arms around me. This is how we show our love. To embrace is to unify. And in embrace, for that moment, we're making one out of two. And in a moment of embrace, the limits of our bodies, our skin, our feelings and our thoughts, are not so clear. And if you look at the two bodies, they blend with each other to some extent. And if you looked, if you had an aerial view of an embrace, two bodies are briefly one. And this is what we see as an embrace. This is what we see as a dance. And this is what we see as a life.

So each of these dharmas is a practice. In a sense, giving is first because they are all forms of giving. And in our traditional action, we give our energies and our cooperation. And these are practices that point towards compassion and embrace. Or maybe more particularly, because we are not separate from each other. And because we are not separate from others, these four dharmas allow bodhisattvas and sentient beings to relieve themselves of delusion in the act of embrace. There is no distinction between self and other, between a bodhisattva and an ordinary being.

But we need to remember that embrace is not simply merging. It's not kind of a mushy and meaningless oneness. We often talk about this. I've been teaching for a long time in the chaplaincy training program at Upaya Zen Center. And at least for our purposes, there's sort of emerged a distinction between empathy and compassion. And this is, you know, that may not, everybody may not agree. It's all, you know, it's kind of premised on how you define words, but the thing about the chaplaincy training is that empathy, sort of one of the primary characteristics of empathy is merging, which is important. Compassion is not quite merging. Compassion is meeting someone in the form that can be liberative. So it's not necessarily becoming them. It's meeting them in a way that is useful. So when an embrace ends, and when this is over, we return, we resume our individuality. But something has changed.

So let's go back. Let's look at in more detail at this first dharma of giving. This is also the first of the bodhisattva perfections or practices, the paramitas. Giving means attention, giving friendship, material aid, spiritual teachings, giving fearlessness. Giving fearlessness is the highest manifestation of dana paramita. And we have all kinds of offerings, right. We offer our voices. We offer our respect. We offer incense and flowers and light and food and all kinds of other things that circulate without anyone holding onto them possessively.

Giving, as I said, includes all the other embracing dharmas. And let me read you the beginning of Shishobo. Shishobo says: "Giving or offering means not being greedy. Not to be greedy means not to covet. Not covet commonly means not to flatter." Which is, that's an interesting move there. So often when we speak, by virtue of our habits we can speak in a way that is currying favor for ourselves. So that's what he's pointing out. "Even if we rule the four continents, in order to offer teachings of the true way, we must simply and unfailingly not be greedy."

And then there's a series of really interesting propositions. It's like offering treasures we are about to discard. And then we're going to give them to those we don't know. Which always makes me think of the things from our household that we put out on the margin by the street. And somebody always takes them. So to offering treasures we're about to discard to those we don't know, we give flowers blooming on the distant mountains to the Buddhas. That is really powerful. Because we live in a different age. I think that in Dogen's time, it was assumed that flowers would bloom on the hillsides and that they were precious to those viewing them and to the Buddhas as well. You know, this was before the era of logging and strip mining. And now we really have to think about this. Are we allowing the environment to be such that there's a place for flowers to bloom on those hillsides? Or have we destroyed them? So I think this, we can take that as an admonition that wasn't intended by Dogen, but that fits our circumstances.

"And we offer treasures accumulated in our past lives to living beings." Whatever comes to us, you know, in a sense, I think what this, what this needs to do for me is, how do we, how do we share our privileges? We not hunker down in them. You know, we have, some of us have fortunate circumstances in our present lives. We have, maybe we have education. Maybe we have health. Maybe we have wealth. This is a treasure that has been accumulated in our past lives of other births, but also past lives of our year by year life. And I think that this is one of the, for me, I'll say this is one of the pressing issues in questions surrounding Israel and Palestine. And there's terrible, there's been terrible anti-Semitism hatred of Jews. And they've also been privileges that have come to us. And I think it seems to me that Israelis and Palestinians are locked into a zero sum understanding of their situation. But maybe that's a longer discussion.

And I think that we can be generous with what we have. Whether our gifts are Dharma or material objects. Each gift is truly endowed with virtue of offering. So giving begins, I think, and it's not just giving, it's nothing but giving in the whole universe. The universe and all beings are continuously giving to each other. This is really our true spiritual understanding. And yet this doesn't necessarily, this doesn't happen automatically. And each of us has to see what's there and be able to offer it to others and to cultivate the practice of giving.

And we're given other things. Maybe we're given things that we don't necessarily want. You know, so we're given the taste of tears. We're given corrosive doubt. We're given as we get older, the decline of our bodies and minds. And we're given war. War is right here. Where I get fooled by my self-attachment and privilege. I think the true giving means giving up one small self and surrendering to the large self. Means not hiding. To come back to, I said the highest giving is fearlessness. It means showing others that I'm willing to face my own weaknesses and failures, which are a natural part of me being alive.

We offer gifts and guidance in many forms. And the second thing is at the heart of these teachings is understanding that what we see of as peace is connection. On the highest level, there's just connection. The endless society of beings. And there's a wonderful book that I've really valued for a lot of years. Maybe some of you read it. It's called "The Gift" by Lewis Hyde. Does anyone know it? It's remarkable. It's a remarkable book. And Lewis is a, he's a Buddhist, he's a philosopher, you know, it delves into psychology and also into anthropology. "The Gift" is what it's called.

So, in this book he describes dinner in a village restaurant in the south of France. He writes, "The patrons sit at a long communal table, and each finds before his plate a modest bottle of wine. Before the meal begins, a man will pour his wine not into his own glass, but into his neighbor's. And his neighbor will return the gesture, filling the first man's empty glass. In an economic sense, nothing has happened. No one has any more wine than they did begin with. But society has appeared where there was none before."

So, when you go to Japan and you're having sake or you're having tea, you pour that for each other, right? And then there's the parable of hell, where beings have arms that are, you know, like five foot long forks. And they starve to death because they can't get the fork into their mouth. But those who are awake recognize, oh, we can feed each other.

So, the gift is only a gift so long as it remains in circulation. So, you think about the Buddhist tradition. It's a wonderful tradition and it's still completely alive in South and Southeast Asia. A monk or a nun carries an empty bowl from house to house. Or, like some of us, I don't know what you all do. We eat with oryoki. Do you do that? We're just bringing it back now after the pandemic. And we are served. That bowl is emptiness. And in this world, food is offered so that we may live. Food is form. The bowl is emptiness. Emptiness and form embrace each other and dance. And then having eaten, the monk, nun or practitioner transforms food into action, which is then offered circularly to serve all beings.

So, giving is not an abstract thing. It occurs in the world itself. Dogen writes, "To provide a boat or build a bridge is offering as the practice of dana-paramita. When we carefully learn the meaning of giving, both receiving our body and giving up our body are offering. Earning our livelihood and managing our business are, from the outset, nothing other than giving. Entrusting flowers to the wind and entrusting birds to the season may also be the meritorious activity of giving." Again, the climate emergency that we're living in makes these particular points really poignant. Entrusting flowers to the wind and entrusting birds to the season.

In all our worldly activities, we should consider what others need and what we can give without coveting, without flattering ourselves, and without nourishing our own self-centeredness. This is always really difficult practice. Dogen says bluntly, again, this piece, it's a great moment when he writes, "The mind of a living being is difficult to change." It's kind of one of those duh moments. The mind of a sentient being is difficult to change. That's true. We know that. This is true for others and it's true for ourselves.

So whether we are doing this, we cultivate it as we are sitting zazen, but it points to the fact that zen is not just about immobile sitting. It's really about how are we living and how are we enacting the bodhisattva vow to save or to awaken with all beings. And we have to build this up. We may have to build this up in a granular fashion, but the question applies to all the great issues of our world. And each of us is a part of this. And we have to build this up. We may have to build this up in a granular fashion, but we can do whatever small part is available to us.

I really like the saying by Suzuki Roshi, which was initially used as a title of a book, which they changed the title. I think they made a mistake to me. But the saying is to shine one corner of the world.

And maybe that corner is very small. Maybe that corner is just one thread of the limitless tapestry of existence. But we can do that. We can pick up that thread and we can weave it into the whole cloth.

So thank you for listening. I'll stop there. There are three more of these Embracing Dharmas, but you may have to figure this out for yourself. I'd like to open for questions or comments.