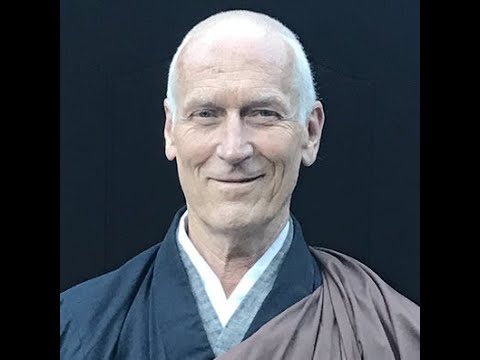

Hozan Alan Senauke — The Dharma of Listening and Speaking

Santa Barbara Zen Center is pleased to offer the teaching of Hozan Alan Senauke: "The Dharma of Speaking and Listening".

Hozan is abbot of Berkeley Zen Center, successor to Sojun Weitsman Roshi. He is founder of Clear View Project, former director of Buddhist Peace Fellowship, and serves on the board of the International Network of Engaged Buddhists. In other realms, Hozan is a musician, writer, activist, and father—not necessarily in that order.

Hozan is the author of The Bodhisattva’s Embrace: Dispatches from Engaged Buddhism’s Front Lines, Heirs to Ambedkar: The Rebirth of Engaged Buddhism in India, and Turning Words (forthcoming from Shambhala). His most recent recording is Everything Is Broken: Songs About Things as They Are.

Full Transcript

So we're very happy to have with us today, Hozan. And I'm going to let Joel introduce his old friend. And right after that, we will chant the Gatha on opening the Sutra. So I'm going to share the screen now so that we're ready for that. But please go ahead, Joel.

Okay. Well, thank you, Hozan. It's wonderful to have you here. Actually, again, you were with us maybe 10 or so years ago when we were at Tony's house, quite a few times. Alan is now Abbott of Berkeley Zen Center and long decades, long practitioner and amazing friend for many years. He does so much. He is, in addition to being an amazing Zen teacher, for decades a social activist. And he's been working with Rohingya refugees and with the Dalits, previously known as the Untouchables in India, and a tremendous, I think, founding member of the Buddhist Peace Fellowship. And also a wonderful musician. Plays with Tar Sings, folk musician, amazing. And he also when he came, Tony O'Hansen, whose house we sat at, was a wonderful folk musician, and they would make a lot of music together. So welcome, Hozan. Thank you for being here.

Gatha on opening the sutra:

The dharma incredibly profound and infinitely subtle

is rarely encountered even in millions of ages.

Now we see it, hear it, receive and maintain it.

May we completely realize the Tathagata's teaching.

Well, good morning, everyone. I'm really happy to be with you here on this early fall morning. I wish that I were with you in Santa Barbara, which is a beautiful place. For a number of years, as Joel said, I used to come down annually and do a weekend with, I guess, an earlier version of this group. I don't know if any of you participated in those sessions. It was wonderful to be up in the hills in Tony and Rachel's house, and sometimes I would come down with my family and we saw that as a kind of busman's holiday. And it'd be wonderful to come down there again.

So this morning, the subject of my talk is on basically the dharma of listening and speaking. And what this arises out of is maybe some of the challenges of communicating on Zoom and online for the last getting on two years, and also issues that have arisen in our sangha, circumstances in which there were really some challenges in how people were speaking, how other people were hearing and responding to those people. And so this talk kind of flows from a talk I gave at BCC about a month and a half ago. It's been revised, but I think the essence is the same.

So obviously in these contentious times, our public and private words can wound or heal. We have this addressed by the practice of right speech, which is the third step on the eightfold path, because some of us, and we have a whole segment of our bodhisattva precepts that are devoted to issues of how we speak. The fourth precept, the sixth precept and the seventh precept. I'll talk on those later.

So how we speak and how we listen is of course essential to our relationships, our relationships in person, in society and in the sangha. Now I'm going to begin by speaking about listening. Maybe I should be listening about speaking, but I think it's important to understand that what each of us hears is not necessarily what a speaker may have meant when they were speaking.

So this points us to a really useful principle that I think was freshly articulated for me only a few years ago. I was teaching at the East Bay Meditation Center, here in Oakland, and they have a series of guidelines for speech and for relationship. One of them highlights the attention that is needed not just to our intention in speaking, but to really consider the impact. And that was, it seems kind of obvious, but that was really a wake-up moment for me. I think that in Buddhism, the emphasis is on intention, and we'll get into that when we get to the speaking part, but that aspect of speaking is explicit. The other side, which is perhaps the large part of the iceberg that's underwater, is that we pay attention to our intention because we know that our words have impact. And so to consider the impact, to consider how someone hears it, is really important. And actually to me, the two go together.

The other side of that is that if we overemphasize impact, then we are likely to arise perhaps from our woundedness, and not to consider what the speaker might have intended. Now, they may have said something unintentionally hurtful, but what we want to do is look at all of this together.

[Technical interruption addressed]

So we're considering impact and intention together. But I want to begin, let's come back to the space of Zazen. And in that, I reflect on the title of one of our teachers, Dainin Katagiri Roshi, his first two books. And this is, I think, an approach to practice. His first book was entitled, Returning to Silence. And his second book was entitled, You Have to Say Something. Now, it may be, I encourage you to read these books, but even if you don't read these books, just consider the titles, because the titles themselves are sort of bookends of our practice.

So, Returning to Silence is hearing. Listening. It's stepping into this open and receptive mind of Zazen. Listening is the active component of hearing. I think that as we practice Zazen, and as we practice Shikantaza, all of our senses are open and receptive. They're not necessarily active, but we're hearing, not necessarily listening, but we can turn our attention there anytime. The same thing, we're seeing without necessarily looking. And we are thinking without necessarily putting together those thoughts into a narrative. We're just taking thought after thought.

So, if I listen for a moment. Oh, I'm hearing actually, in the apartment next door, Ross is listening to the service, the Saturday service that's taking place right now at BCC. So, I hear the heart sutra. I hear the birds and the trees. I hear a car going by. I hear the little fan in my computer. And what I realize is that this listening takes place against the background of silence. And so, as I listen and hear, then I can return to the silence at the same time.

There's of course a wider frame for this. This is bodhisattva practice. The bodhisattva Avalokitesvara or Kuan Yin or Kannon is sometimes referred to as the one who sees the cries of the world. I love this expression because it suggests that in her practice and in our zazen, with all of our senses functioning, there can be a kind of synesthesia. There can be a way of experiencing one sense in the workings of another. That is what my teacher Sojun Roshi spoke of all the time was to include everything in zazen.

And so to return to silence is, I think, the all-inclusive experience of zazen. But zazen mind is not confined to the walls of the zendo or to the frame of this zoom screen. I like the zoom screen actually because unlike the zendo, we can all see each other. And there's a new practice to that. Anyway, the full unfolding of zazen is in our life. And in our life, we're bound to have some activities. We have to do something and inevitably we have to say something. This acting and speaking is also proceeding from zazen mind. And we're always moving between the silence and the sound. Between the stillness and the activity. This is really a continuous circle of the way.

So I recently came on an excerpt from a 1967 lecture by Suzuki Roshi where he speaks about the practice of listening. He says, when you listen to someone, you should give up all your preconceived ideas and your subjective opinions. This is very hard as we know. You should just listen to him or her. Just observe what his way is. He says we put very little emphasis on right and wrong or good and bad. We just see things as they are with him and her and accept them. Also very challenging practice. This is how we communicate with each other. Usually when you listen to some statement, you will be able to hear it as a kind of echo of yourself. You're actually listening to your own opinion. If it agrees with your opinion, you may accept it. But if it does not, you reject it or you may not even really hear it.

I think we can all really understand exactly what Suzuki Roshi is describing. Not that any of us do that, but we've seen somebody who doesn't. Suzuki Roshi is suggesting that we ratchet back on what we've been doing. Our habit of judging everything that we listen to. Of evaluating right and wrong or good and bad. He is not, to be clear, suggesting that we abandon morality. I think what he's pointing to is that usually when we judge right and wrong, good and bad, there's some self-centered frame of reference. What he's suggesting is see if you can set that aside.

What I find is when I do that practice, I set it aside, then I can learn something else about the person who is speaking. In the moment of listening, we can try to see the cries of the world. Just see that person as he or she is right there in that moment. Don't make up a story about the way they always are or always have been or are going to be in the future. Just how is it right now? Of course, how is it right now is precisely the experience of Zazen, but this is a way that we can take it out into the world. Whether I agree with the person who is speaking or not, can I make an effort to accept him or her? I think that's a good question.

Thich Nhat Hanh speaks of this in one of his mindfulness trainings. His mindfulness trainings are his gloss on the precepts. He refers to them as mindfulness trainings, which is a very useful way of looking at it. It transforms what we might easily take as a rule or a commandment to an actual practice. His fourth mindfulness training is what he calls deep listening and loving speech. He begins by saying, aware of the suffering caused by unmindful speech and the inability to listen to others, I vow to cultivate loving speech and deep listening in order to bring joy and happiness to others and to relieve others of their suffering.

So I think that how we listen and how we speak is the heartbeat of a practical Zen Buddhism. It's true that the silence is deep and nourishing, but when we think about it, we inhabit that space for a relatively small part of the time. Much more of our day is spent interacting with each other, not being fully aware of the silence that is always there. So even as we speak, we should always be listening.

Thich Nhat Hanh's commentary continues, and here we move from listening to speaking. Knowing that words can create happiness or suffering, I vow to learn to speak truthfully and to be open to others. Knowing that words can create happiness or suffering, I vow to learn to speak truthfully with words that inspire self-confidence, joy, and hope. I am determined not to spread news that I do not know to be certain, and not to criticize or condemn things of which I am not sure. I will refrain from uttering words that can cause division or discord, or that can cause the family or community to break. I will make all efforts to reconcile and resolve all conflicts, however small.

This is a wonderful and really difficult place that he goes to, and we can see the difficulty in our own society. And sometimes it's true, we can see it in our family situations, in our sangha situations. Reconciling all those conflicts is really hard. It's highlighted, I think, in the sharply outlined conflicts that we see in our society now. I can hardly remember a time, well, I can remember one time, certainly going back to the 60s, when the society seemed split down the middle. In relation to, particularly in relation to the war in Vietnam. But we have fresh divisions, or the highlighting of divisions that were always there in our society right now, and they're very hard to reconcile. And it's very hard to hear certain of the views of the society, and it's very hard to hear certain of the views that we encounter and see the people who are projecting those views as Buddhists. This is really hard.

I think that speech is like an arrow, that once it's released, it cannot be called back. It's not like getting into a fist fight where you can pull your punches, even in the midst of the contention. Once you've released that arrow, it's going to go where it aims. And when it, if it strikes its target, it's going to cause a wound. And if that wound is there, even where there is subsequent healing, there's often a scar. Or sometimes this is called proud flesh. I think that's the expression. Is that right? And so proud flesh shows and perhaps is a bit more tender than the unscarred flesh around it.

So what this says to me is that when words have been spoken in contention or in anger, and they reach their mark, there's always going to be a sensitivity there. Now we live with that. That's not necessarily a bad or unavoidable thing. But it's something to take into account. So before you put that, before you pull that arrow from your quiver and notch it up on the bow, you might think about what the long-term ramifications are going to be in releasing that arrow.

So the Buddha talks about this when he talks about speech. And it's very interesting. You find this in, it's in quite a number of places in the Pali sutras. And particularly in, you can find it in the Abhaya, Abhaya Sutta, which is in the Middle-Length discourses. Basically, his recommendations for speech is that you should speak when something is true, useful, timely, and with a kindly or beneficial intention.

So I'd read, let me read you a little of his commentary. In the case of words that the Tathagata knows to be unfactual, untrue, unbeneficial, unendearing, and disagreeable to others, he does not say them. Well, that's pretty obvious. Words that the Tathagata knows to be factual, true, but unbeneficial, unendearing, and disagreeable to others, he does not say to them. Words that the Tathagata knows to be factual, true, beneficial, but unendearing, and disagreeable to others, he has a sense of a proper time for saying them, and so on. The Majjhima Nikaya does this kind of wonderful analytic parsing of the various circumstances under which one might speak.

Now, one of the things that occurred to me, and perhaps this is a distinction as we move from early Buddhism at the remnants of which we have in the Theravada school and Mahayana teachings is that there's very little ambiguity in early Buddhism. It's quite binary. It's this, not that. And so true, useful, timely, and beneficial for the Buddha were concrete realities. And for him, actually, there was no distinction of intention and impact.

For me, there is. Sadly, owning my, well, let's say my partial enlightened nature, which is maybe giving myself the benefit of the doubt. But when we look at it, we consider true. Well, what does that mean? It implies in the Buddha's terms a kind of absolute, but what's true for me may not be true for Joel. And so that applies down the line. What's true, what's useful, what's beneficial or timely. All these things are, we live in a realm of subjectivity rather than a realm of absolute certainty. And so we come back actually to intention.

We weigh our words against what we might think is going to be the impact. We try to move as close as we can to the truth while knowing at the same time that there is quite possibly some untruth or some, or the moment may not be timely. It may be timely for me, but it may not be timely for you. So this is this subjective realm of our practice that's very difficult.

And I think it calls for, along with speaking, asking. Asking permission to say something. Asking, how did you hear that? And I think that's quite wonderful because when you ask along with the words that you offer, then you're actually inviting relationship. You're inviting dialogue.

And I think it goes back again to one of the essential teachings that we receive from Sojan Roshi, where he was saying that the Zen question is not why or what, it's how. How are we going to do that? The Zen question is not why or what, it's how. How was this for you? You know, I'm doing my best to say something that's true, but what do you think? How is it what I said? And to go into that with a spirit of inquiry.

I think about this line that I love from, I think it's from the Jomir Samadhi. The meaning is not in the words, it responds to the inquiring impulse. The inquiring impulse is exactly what creates relationship. And it's our relationship to ourself and to all around us that is at the heart of our practice. It's not about, practice is not about some cataclysmic experience. It's, that may happen, but it's made up of these small, small questions and the ability to question is actually the expression of our Buddha nature.

And this is just to say, this is a Buddhist principle, but what I've discovered and can go on in another context, in another time, I discovered there is a tremendous literature of this in the Jewish tradition, in the Talmudic tradition. There's a whole discourse, a long discourse on speech and wrong speech called Lashon Harah. And it's quite amazing because much like you find in the Vinaya texts, if you've read those where there's a gloss on every one of the 250 or more precepts, kind of stories about where they came from and what they imply, the same kind of detailed, usefully detailed stories are told in the Talmudic tradition. About every nuance of inappropriate speech and how we rein ourselves in.

So that's just a little about listening and speaking. If I'm following the schedule I've been given, I'm going to stop here and leave time for questions, answers, comments. Is that, is this the moment for that? Yes, thank you, Hassan, so much. And Sangha friends, if anyone has a question or comment, please unmute yourself.

I'm going to remind our Sangha of some community agreements that we're in the process of forming. But one of them I hope you will remember in this moment is that if you usually are the one who comes out and speaks, please leave a little room for those whose process might be. Take a couple of seconds and let others speak. And in particular, pay attention to follow up questions because sometimes I know we get into the next layer and the next layer and the next layer and that basically locks other people out from the opportunity. So having said that, please come forward and ask your questions and comments. I don't want to, I don't want to mute anybody, but I want you to be aware that we are Sangha. Thank you.

So I'm not sure how this works. Do you call on them? Do I call on them? Do people raise actual hands or digital hands? All of the above actually, depending upon where people are coming from. So we kind of allow whatever happens to happen. And if I see somebody and you don't, I will call on them. And if you see somebody and I don't, how's that? We'll just do a totally fine open the doors.

Well, I guess I'm going to go because I think I've persuaded everyone to wait and it's going to waste too much time. I'm sorry. I was, I was highly effective. I didn't need to be. Hozun, I really appreciate this talk and I noticed lately that I, and I will go get up and I'm going to go get up and make the offering. As soon as you're ready.

May the merit of our practice be directed towards lasting peace in ourselves and in the Sangha, tranquility of daily practice, dissolution of all misfortune and fulfillment of all relations. Sentient beings are numberless. I vow to save them. Desires are inexhaustible. I vow to put an end to them. The dharmas are boundless. I vow to master them. The Buddha way is unsurpassable. I vow to attain it.

Okay, thank you everyone. I'm going to make a couple of announcements.